Maggie Alphonsi: The day I smashed Owen Farrell in training

I could tell from the look in Owen Farrell’s eyes that he wasn’t going to pass the ball. He may have just been 18 years old, but the future captain of the England men’s team already looked the part, sporting a Justin Bieber-style floppy quiff. I’m sure he regrets it now. But even back then he had an aura about him. Everyone knew that his father was Andy Farrell, the rugby league legend who had decided to finish his playing career in rugby union, for Saracens and briefly for England. But Farrell junior was the future now. And he knew it.

His team-mates no doubt probably thought he was a bit up himself, but I could tell his overly confident demeanour wasn’t misplaced. He was a player going places, and quickly. And he had no intention of letting me get in his way. It didn’t matter to him that he was training against a woman – he quite rightly saw me as nothing more than an opposition player with a weakness that he would find and ruthlessly exploit. All he needed to do was make the pass, but I think when he saw that I was the defender he thought: ‘I’m just going to run at her’.

I knew who his dad was too. But, on that freezing Tuesday night at the University of Hertfordshire grounds in Hatfield, I knew I only had one job. Ringing in my head was the phrase I’d heard, over and over again, from Geoff Richards, a tough-talking former Australia full-back who had been instrumental at the start of my international playing career during his time as head coach of the England women’s side: ‘Make the f------ tackle, Maggie; make the f------ tackle.’

If I knew who Owen’s dad was, he certainly didn’t know anything about me. Why would he?

It was March 2009 and Farrell was the rising star in the Saracens academy that was being compared to rugby union’s equivalent of Manchester United’s legendary Class of ’92 that included David Beckham, Nicky Butt, Ryan Giggs, Gary Neville and Paul Scholes. Saracens’ equivalent was similarly sprinkled with stardust; Farrell’s team-mates included future England and Lions forwards Jamie George and George Kruis, as well as Jackson Wray and Will Fraser, who would go on to play in the Premiership and in Europe.

They were all thriving as part of an uncompromising regime headed up by an equally uncompromising Eddie Jones. The future England head coach was in charge of Saracens then, and that night I was also given a unique insight into his forthright and challenging approach that would ultimately cost him his job with the national side more than a decade later.

To be fair to Eddie, he’d welcomed me into the fold. At the start of the 2008/09 season, the Rugby Football Union for Women (as it was known until we merged the RFU in 2014) had felt that the England Women’s squad would benefit from taking part in training with the club academies from the men’s game. As I already played with the Saracens’ women side – along with veteran internationals Amy Garnett and Karen Andrew – I’d been invited to take part in the training session with the Saracens academy. There was just one condition. When the coaches asked Eddie if it was OK for me to take part in the session, he said: ‘Yes, it’s fine but she’s got to do everything that the boys do, though.’

I had no problem playing against the boys. In my wilder, childhood years, I’d squared up and fought against boys much tougher than that Saracens bunch on the patch of ground at the back of my block of flats in the Edmonton estate in north London, where I grew up. It was just the way of life back then. You had to stand your ground, even for those of us like me who didn’t join a gang, whether you were a boy or a girl, because reputation was more important than your gender.

I’d also developed a bit of a relationship with the lads because I’d been to a few sessions before, and they appreciated that I was there to develop my skills. The problem was that on the very night that Eddie turned up, neither Karen nor Amy had been able to make it. I was on my own.

I travelled to the sportsground already in my kit so there was no awkwardness about changing before training, but I can remember getting out of my car and thinking: ‘Do I really want to do this?’

Rugby players, men and women across the country will recognise the feeling. One of those nights when you don’t fancy it. But as I knew I was the only woman turning up, I knew I had to. There was a burning ambition too. This was the sort of opportunity that I knew was special and that if I wanted to develop my game and progress further I had to do it.

I kept talking myself up as I slowly pulled on my boots: ‘I can do this; I can do this.’ When I saw Eddie was there too, I knew my reputation and that of the women’s game was also on the line. Come on Maggie, you’ve got this.

It was a bloody hard session. Lots of running, a lot of hitting the floor and getting up again. If anyone dropped the ball, our punishment was to do some laps of the artificial pitch. I was embedded as one of them. In a weird way it was a good thing I was the only woman that day because I knew I had to step up and be visible – and I wanted to step up.

The tackling sessions were no problem. It might be hard to understand if you’re a woman who has never tackled a man or a man who has never tackled a woman on the rugby pitch, but I’d been used to playing against some really big and physical women so I knew I could look after myself.

When people meet me nowadays for the first time, quite often they will comment on how small they think I am. And I grew up wanting to be like players like Selena Rudge, who played for Wasps and won 47 caps for England. She was so strong and combative, like a mixed martial arts fighter blessed with rugby skills who would never take a backward step. Put it this way, you would never want to get into a ring with her. And she had thighs like Joe Cokanasinga, the Bath and England centre. When I tried to tackle her, it was like trying to stop a bus, she would pretty much run people over.

I was 26 when the RFUW had us train with the Saracens academy, so tackling 18-year-old men didn’t strike me with any fear.

But Farrell was big for his age. He was taller and had a way bigger stature than me. The drill was three attackers versus two defenders. The defenders were outnumbered but had to make the right decision and make the tackle. When Farrell received the ball, it was my turn to defend. Make the tackle Maggie. Make the tackle.

He had one player outside him. He ran at me hard. I lined him up, with the perception that he was going to pass, but in the moment, I knew that he had no intention of passing. I can understand why.

But of all my abilities on the rugby pitch, tackling was my core strength. It had been drilled into me from my first days in rugby. It would go on to earn me the nickname ‘Maggie the Machine’ for my defensive work in the World Cup final in 2010, coined by former England internationals, Stuart Barnes and Dewi Morris who were on commentating duties that night when the game was broadcasted live on Sky Sports.

Before every tackle I made, I would always run through my options. Do I go low and just make the leg tackle? But that felt too risky. What if he stepped me? Do I hit him near the hips? But there was risk involved in that too, as he could simply offload to the extra attacker. No, there was only one option. I was going to have to go for man and ball. Literally. It may not have been the most amazing tackle in the world, but I remember hitting him and, in the collision, stopping him in his tracks before grabbing and pulling him down in the tackle.

I still remember to this day the coaches on the sidelines gasping: ‘Oh my God, she has just taken down Owen Farrell.’ The other lads loved it too.

The assumption was that Owen wasn’t too happy about being tackled. Owen should have passed, and he didn’t run at me again.

But at the time there was no other major reaction. I’d just done my job. I was meant to have made the tackle, just like Geoff Richards would have wanted. When you’re with the lads, you just get on with it. There was no pat on the back. The reality was that I’d been supposed to make the tackle. All I cared about was not missing it. That one was for you, Geoff.

Looking back now I recognise that session as one of the defining moments of my career. I wanted to step out of my comfort zone and, in the moment, I’d stepped up. I learnt something about myself that night and grew from it.

To have executed the tackle in front of Eddie Jones made it all the more special. He’s not renowned for giving out praise.

But in the feedback from the session to the RFUW he said the words that I desperately wanted to hear: ‘She fitted in like she was one of the lads. She did well.’

I’m not sure Owen or Eddie remember the moment now, but it stayed with me for the remainder of my career. Nowadays when I meet Eddie, I still have no idea if he knows it was me who made the tackle that night.

But on that Tuesday night in Hatfield, I felt I’d earned his respect. Owen’s too, and the respect from the other lads who were in attendance that night. It was another staging post for me and left me with a feeling that fired me on through the high and lows of my career.

I just remember thinking that night, not for the first time: ‘I’m just going to be one of the lads. I’m going to train harder, run harder and tackle harder than any of them. There’s no gender. I’m going to stand my ground and never take a backward step.’ You don’t mess with Maggie. Even if you’re a boy.

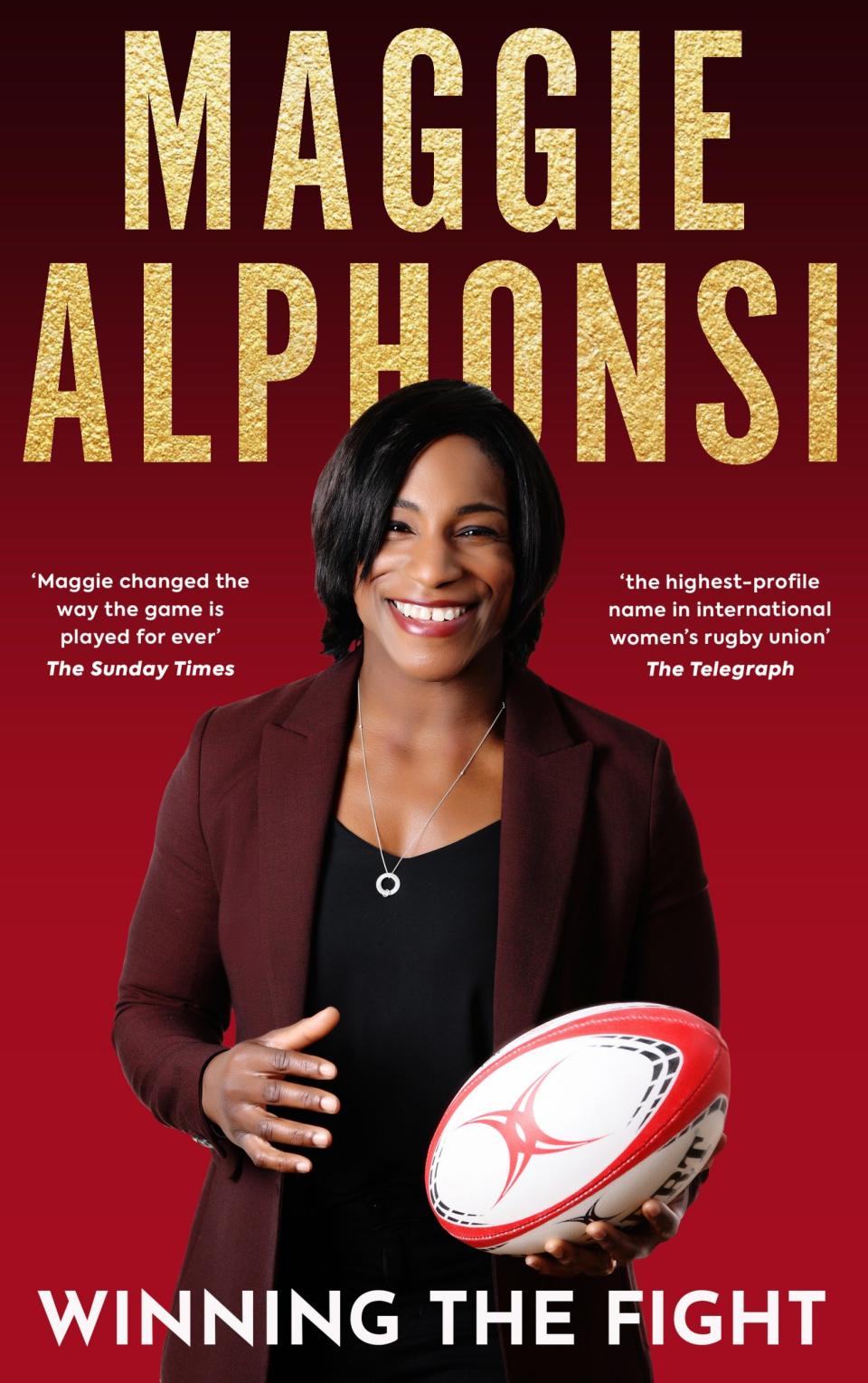

Maggie Alphonsi: Winnning the Fight is available to preorder now from all good bookshops and online. Available to buy from Aug 31.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport