Mo Farah insists he was tested for drugs at African training camps

Mo Farah has insisted he had frequent blood and urine tests during high‑altitude camps in Kenya and Ethiopia – and has never seen any of the shady practices exposed by Asbel Kiprop after his positive EPO test.

Kiprop, an Olympic gold medallist and three-times world champion at 1500m, said this month that he had been tipped off in advance before a drug test and had paid money to doping control officers. Those claims, along with his positive test, sent shockwaves through the sport – and raised serious questions about whether athletes in east Africa were being properly tested, with the independent Athletics Integrity Unit confirming that the tip-off took place.

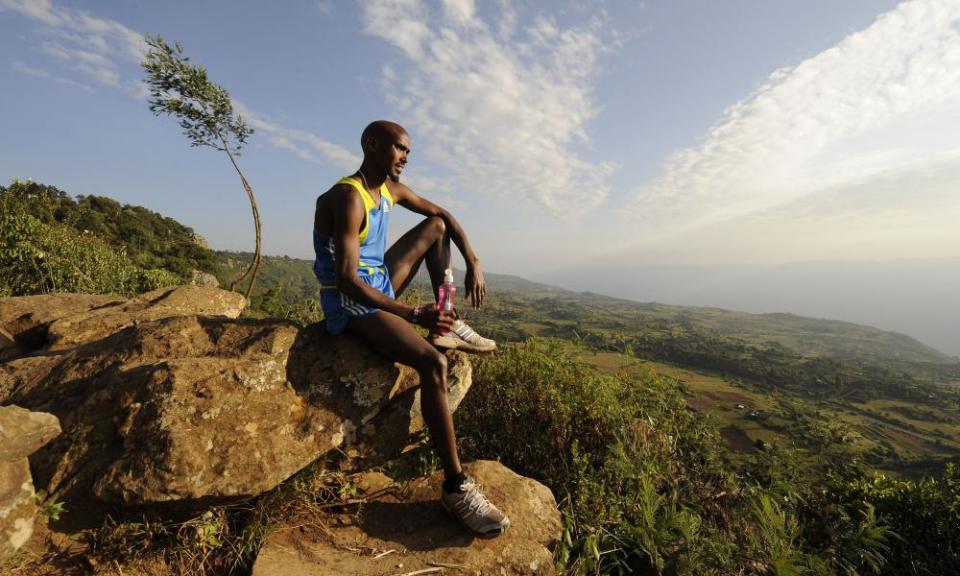

However Farah, who trained in Kenya up to 2014 and has subsequently done much of his winter preparations in Ethiopia, said he has been rigorously tested in both countries.

“When I was in Ethiopia training for the London marathon I was pretty much tested on average every two weeks, and maybe even more than that,” he said. “And when I was in Kenya I was tested a similar amount, although I haven’t been since 2014.”

When he was asked whether that included both blood and urine, Farah replied: “Yes, and the same in Ethiopia.” Farah also denied ever being asked for money by doping control officers. “No,” he replied firmly. “And for me there are a few things wrong with the Kiprop situation. First, the drug testers are not there to give you warning – they are there to surprise you and to catch you, otherwise what’s the point in testing? Second, why is anyone coming for money? That’s breaking the rules. Third, he failed a test.”

But Farah, who set a British 1500m record of 3:28:85 when finishing behind Kiprop in Monaco in 2013, admitted the latest big-name positive was desperately bad news for athletics. “Yes it is, but that’s our own fault. In this sport, because it has some negative things about it, people do ask questions of someone who has run certain times. The first thing you do is think: ‘Oh, God, has it become normal now?’ But at the same time we have to keep fighting. I just look back and you just hope he wasn’t on it when he beat me, but obviously you question it.”

Some have also questioned Farah in the past, given his former coach Alberto Salazar remains under investigation by US Anti-Doping, and his association with Jama Aden, who has been investigated by the Spanish police, but Farah has always insisted that he has done things the right way. He urged the IAAF to step up its anti‑doping work for the good of the sport. “It is a fact that other African countries are not doing what we do,” he said. “And if we don’t deal with it now, how is it going to be for the next generation?”

Lily Partridge, the first female British athlete home in last month’s London marathon, has also urged the IAAF to consider banning Kenya because of the high number of positive tests in the country in recent years.

Partridge, who finished eighth in London, warned: “We can’t lump all Kenyan athletes in the same bracket but we have to acknowledge that they aren’t under the same protocol as we are. And for a country to be so dominant, and consistently dominant, you do have to say that if they don’t have that anti-doping system in place it is open to abuse.”

Partridge said that she would favour a system similar to the one Russian athletes have to go through – where individual athletes have to be approved by the IAAF. “Until they have a system in place it is very difficult to believe or get excited about performances that come out of those countries,” she said. “I don’t want people excluded, but if that is the only way we are going to sort it out then they have to be.”

Farah, meanwhile, who will compete over 10 kilometres in the Great Manchester Run on Sunday, also confirmed he would be running an autumn marathon, most likely in New York or Chicago. And he insisted that his recent third place in the London marathon had encouraged him to think he could win a medal at next year’s world championships in Doha. “If you look at world championships and Olympics the times are not that fast, so hopefully what I did in London shows I can mix it and hopefully win a medal.”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport