Not so fast: The many ways F1 tries to make its cars slower

The Olympic motto is ‘Faster, higher, stronger’ and it’s a motto you’d think could easily be adapted to F1: Faster, faster, faster.

But not so fast… because, as a sport, F1 continually finds ways of slowing cars down.

In the main, this is a safety measure, although there are other reasons – making the sport greener, for example, by consuming less fuel.

So, how fast are today’s cars compared with their ancestors?

Pick a number

The speed that an F1 car laps at depends on a great many factors – everything from its weight and the size of its tyres to the track surface and temperature (the engine and driver can make a difference too…).

It’s popularly accepted that 2004 (Juan Pablo Montoya, pictured) was the fastest F1 season, although Motor Sport magazine used a complex comparison tool called the Pomeroy Index System and said that the fastest season was actually 2002. See, it’s not that easy.

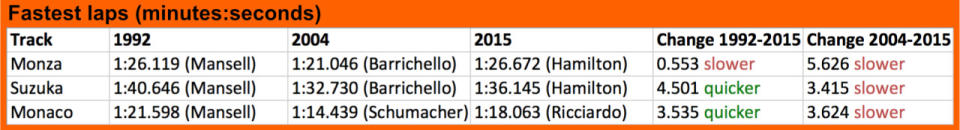

From a spectator’s point of view, the most straightforward way to see how rule changes impact lap speeds is to compare fastest laps from a given circuit, over a number of years, in similar weather conditions.

Not only does this take account of engineering restrictions, it also takes into account changes to circuits eg building a new chicane to slow cars down.

It’s not a perfect approach – there will always be some factors it misses – but, as a rough-and-ready calculator, it’s hard to beat.

With all other things being equal, and no rule changes, you’d expect F1 teams to lap marginally quicker each season or, at the very least, plateau at the same level of performance as the previous season.

Over the last few decades, though, there have been periods where rule changes have altered lap times quite markedly.

Let’s take three very different circuits and look at the fastest laps last season, in the super-fast 2004 season, and a further 12 years before that in the 1992 season.

Taking all aspects of F1 into consideration – track changes, engine changes, aero changes, everything – last season’s top lap at the superfast Monza circuit was slower than in both 2004 and 1992.

At super-twisty Monaco and the challenging Suzuka circuit, it was a different story. The fastest lap was markedly quicker at both in 2015 compared with 1992 – but still significantly slower than that 2004 season.

Now, faster laps don’t necessarily equate to more exciting racing but that’s a topic for another day. What we do know is that cars have been faster in 2016 than in 2015, so the gap to 2004 has closed a little more.

For those who believe F1 should be as fast as possible, next year’s rule changes are predicted to knock three to six seconds off lap times.

So, yes, those lap times could still be slower (just) than in 2004. Or they could, for the first time, eclipse 2004 lap times, though perhaps not at fast circuits such as Monza, where downforce and tyre wear are of less significance.

Will extra speed bring extra ‘wow-factor’? Only time will tell.

Rules, rules, rules

Every season, and sometimes mid-season, the FIA change the restrictions that F1 teams face.

Sometimes, these changes are to encourage quicker laps and a more exciting spectacle.

Often, though, they are to restrict speeds, either directly – by limiting engine RPM, for example – or indirectly – restricting the number of engines a team can use in a season.

Some of the rules that can slow cars down include:

Fuel – F1 fuel is 99.5 per cent identical to the fuel you stick in your own car. But, then, your DNA is 99.5 per cent similar to Usain Bolt’s and, for that matter, Lewis Hamilton’s.

That last 0.5 per cent makes all the difference, to us and to the fuel in an F1 car. But, once upon a time, F1 cars were allowed to run on pretty much anything. Aircraft fuel, benzene, all manner of hellish cocktails were used to power early F1 cars.

Some fuel mixtures were so unpleasant to deal with that, after a race, the engine would be washed in ordinary petrol to stop the race fuel from eating the metal away.

Refuelling (pictured) has been allowed at points in F1 history – running with tanks no more than half-full cuts average race times but doesn’t impact as much on fastest laps as might be expected, as the cars still weigh the same at their lightest.

Fuel flow restrictions and a limit on how much petrol can be used in each race (100kg at present but rising next season) have a big impact on average speeds as drivers manage fuel usage by using less thirsty engine modes, and by ‘lifting and coasting’ – coming off the accelerator early before a corner.

But teams can still ‘turn up the wick’ to burn some extra fuel if need be so, again, the impact on fastest laps may not be quite as large as expected.

Engines – Perhaps the most obvious rule restrictions affecting speed have been to do with engines. F1 engines have been permitted in various guises from 750cc to 4500cc (in the early days).

Restricting RPM (in 2007-08 initially) did slow F1 cars a little but the aim was to reduce the number of engines being blown up by teams, and control costs.

These days, of course, ‘power units’ include 1.6-litre V6 engines, turbos, energy recovery systems, plus electrical storage and computer trickery – all of which are tightly regulated to limit just how much speed teams can extract from their cars.

Tyres – Next season’s F1 tyres will be about 25 per cent bigger than this year. That means a greater surface area in contact with the track, higher cornering speeds and tumbling lap times.

But tyres have also been used to slow cars down. From 1998 until the end of 2008, F1 cars ran on grooved tyres, specifically to make them slower – using grooves meant there was less rubber in contact with the track and that, inevitably, meant less grip.

While the tyres did have a marked effect on lap times, teams adapted quickly and almost completely offset the losses from grooved tyres (and other rule changes, such as making the cars narrower). The result? Another rule change for the following season, when an additional groove was mandated.

Aerodynamics – If the rules governing aerodynamics have a primary function, it’s to limit how rapidly cars can corner.

High cornering speeds are tough on drivers and, if anything goes wrong, a big accident is far more of a risk.

But the aero rule changes for next year aren’t just about controlling cornering speeds. The teams and Bernie Ecclestone wanted more aggressive-looking cars which weren’t affected so much by turbulence, and the new, wider and deeper front wings reflect that.

The rear wings will be lower and, coupled with new diffuser rules, will help to anchor the car to the road more effectively – so these rule changes should help cars lap quicker.

In fact, at Silverstone’s superbly snaking Maggots-Becketts complex, cornering speeds could leap from an already impressive 105mph to 130mph.

And that’s the difference rule changes can make to the speed of an F1 car.

If you can’t control it, ban it

F1 has a long and, often, frustrating history of banning devices which improve a car’s performance.

Here are just a few:

Skirts – In the late 1970s and 1980s, cars had a bit of bodywork that reached down to the ground and helped suck the vehicle on to the track. ‘Ground-effect’ cars were cornering at speeds approaching what drivers could safely cope with and there were some terrifying accidents.

The speed advantage they offered was huge – the pole lap at Silverstone in 1979 was 6.6seconds quicker than in 1977, and most of that was credited to the ground effect.

In 1981, skirts were banned, but teams found a work-around (it turned out they were still legal if you lowered them after leaving the pits) and they were made fully legal again in 1982.

It was a costly decision – the brutal nature of ground-effect cars was implicated in the death of Gilles Villeneuve; at the Brazilian Grand Prix, Nelson Piquet (pictured) collapsed on the podium, exhausted by the effort of controlling his Brabham in the Rio heat, while his team-mate Riccardo Patrese retired from the race, disorientated and physically spent for the same reason.

At the end of the season, ground-effect cars were banned again; F1 had learned that it’s pointless making cars go faster if the forces involved are too great for drivers to bear.

Turbos – After a difficult gestation, the first turbo era in F1 produced the most fearsome cars ever to grace the sport.

Power output was as high as 1400hp, speeds were far beyond what was safe, and engines were built to last just a few laps of flat-out qualifying – they were nicknamed ‘grenades’, because they blew up with such regularity.

Because of the huge power output, cars could run with steep wing settings, producing extreme downforce that allowed them to corner more and more quickly.

The speeds were too high, the costs were too high and it was proving difficult to police turbos. They were banned at the end of the 1988 season, and wouldn’t reappear until 2014.

Active suspension – This was initially developed as part of the ground-effect revolution in the early 1980s, using computers to try to keep cars level with the track at all times.

Like the development of the turbo, active suspension had troubled early years and it had vanished from F1 before the end of the decade.

But more powerful computers helped it return and, in 1991, Williams had a system they were confident would work, although they didn’t get a chance to use it that year.

It was fitted to a 1991 Williams FW14B and, in winter testing, it proved to be so effective that the team opted to stick with their old car for the 1992 season, mothballing the updated FW15.

Active suspension was worth 1.5seconds a lap, a remarkable difference, and Nigel Mansell used it to fantastic effect, most notably at Silverstone where he was three seconds faster than everyone except his team-mate.

Other teams complained, as is the way in F1, but they all developed their own systems for the 1993 season.

Cornering speeds were creeping up again as a result and the FIA decided to act, issuing an infamous edict at that year’s Canadian Grand Prix which decreed active suspension to be a banned ‘moveable aerodynamic device’ and thus illegal.

Once again, the engineers had been beaten by the rule makers.

It’s yet another example of how old technology could make modern F1 cars far quicker round a track – if it didn’t break the drivers first.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport