Paul Ince: ‘I am a big-time Charlie. I played for Man Utd and Liverpool’

Paul Ince is attacking the space between how things happened and how things are remembered and there are plenty of times when it seems to him it is all a little muddled. Take England’s victory over Scotland at Euro 96, in which he played and is an eternal subject of questions for him – even more so now as the rematch looms at this championship.

“People remember it for the Gazza goal which put us 2-0 up and the infamous celebration but they should actually remember it for the Dave Seaman penalty save from Gary McAllister moments earlier,” Ince says. “The save was such a pivotal moment in the win, which changed the whole outlook that the fans and the press had of us.”

Ince feels the same selectivity has gone to work on the semi-final, which England lost on penalties to Germany but only after Paul Gascoigne could not stretch to convert an Alan Shearer cross in extra-time for what would have been a golden goal.

“People go on about the Gazza moment and they say to me: ‘Every time I watch it, I still think he’s going to get there,’” Ince says. “But before that we had a much better chance with Darren Anderton. He should have scored but he slipped and hit the post from about four yards. I’m not saying it’s down to him but how many people keep saying to me: ‘Oh, imagine Gazza had just got his foot to it.’”

More notoriously, Ince remembers how Alex Ferguson made a comment about him in his team-talk before Manchester United’s game with Liverpool in April 1998. The midfielder was playing for Liverpool by then and Ferguson brought him up and “his big-time Charlie bit”. The clip was shown by Granada in a Ferguson documentary that year.

“A manager was trying to motivate his players to perform against a former teammate,” Ince says. “It is normal. Listen, my relationship with Sir Alex is fine. People always kind of think I’ve got this … no. I’ll still go round his house and play snooker with Sir Alex. We have a very good relationship.”

How the phrase was remembered. It stuck to Ince, the reality of the context unimportant. Ten years later, Ferguson would apologise. “Because it was wrong,” Ince says. And yet, on a literal level, it was not.

“Of course I’m a big-time Charlie,” Ince says, at an event to promote Paddy Power’s Euro 2020 fan zones in Croydon and Newcastle. “I played for Man United. I played for Liverpool. I won trophies. I won FA Cups.

“I’m no bigger-time Charlie than Cantona or Keane or Robson. But we are big-time Charlies because when it comes to the big events, we produce. That’s why we’re called big-time Charlies.”

Ince’s failure to produce at Euro 96 is his big regret, although he is not talking about how it ended against Germany because penalties are too open to vagaries, in his opinion. He was down for the seventh kick but it did not get that far when Gareth Southgate missed the sixth. Ince, who sat with his back to goal during the shootout, was criticised for allowing a defender to step up before him.

“People say to me: ‘Why didn’t you take a penalty?’ And I say: ‘I would have taken one after Southy. It was either me then Southy, or Southy then me. One of the two. It didn’t matter.

“I was praying they would finish it off with the first five takers. They were the same from the quarter-final shootout against Spain and I was quite confident they would score. And then it’s just up to Dave Seaman to make a save. ‘Just make a save, Dave …’

“When it goes to six, I’m thinking: ‘Jesus Christ, I’m next.’ You could be the hero, you could be the villain.”

The Scotland game was seismic because of how it swung from close to disaster to igniting a famous summer, uniting England as rarely before or since, and framing the game in a more populist light.

“I remember the MPs saying when they started supporting their team, that sort of thing,” Ince says. “We hadn’t hosted a major tournament since 1966 and it kind of changed everyone’s life that year or that month. Everyone was on a downer and we lifted them. Maybe that was the magic of it all. You could sense that at the tournament. Although not until the Scotland game.”

Before that, there had been the drab 1-1 draw against Switzerland in the opening game. And before that, there had been the Cathay Pacific incident, when some England players caused damage to the plane on the way back from the tour of Hong Kong, which had ended with the drinking session at the China Jump Club, featuring the Dentist’s Chair.

“It wasn’t everyone who was involved in it,” Ince says. “It was certain players but we are a team and we deal with it as a team. When we came back we got absolutely castigated for what had gone on. We were pretty cool about it. Listen, we had lads who had a few drinks. So what? It went a bit out of hand and it shouldn’t have done.”

There was fury and negativity, the sense people might have been waiting for England to fail at the Euros but when they turned it around against Scotland, salvaging what Ince remembers as a performance that “wasn’t great … Jamie Redknapp came on at half-time and changed the game”, it was as if a switch had been flicked.

The change was irresistible. The Netherlands were swept aside and Ince was convinced England would lift the trophy after the fortuitous win over Spain, who the England squad thought the best team in the competition.

“So it’s a bittersweet memory,” Ince says. “You get that feeling, you just know it’s going to be your year. And when it doesn’t happen, you have regrets. Germany, regrets. I look at the whole game and think: ‘How have we not won that?’ We were outstanding and had the chances to win.”

Perhaps the strangest thing about Ince relates to his legacy as a player, how he does not always get the respect he deserves, particularly from United fans. From 1992 to 1995, when he left the club for Internazionale, he was the best midfielder of his kind in the Premier League.

Ince was a one-man wrecking crew in the middle of the pitch. But he also had a remarkable ability to read the game and to drive his team with bursts through opposing lines.

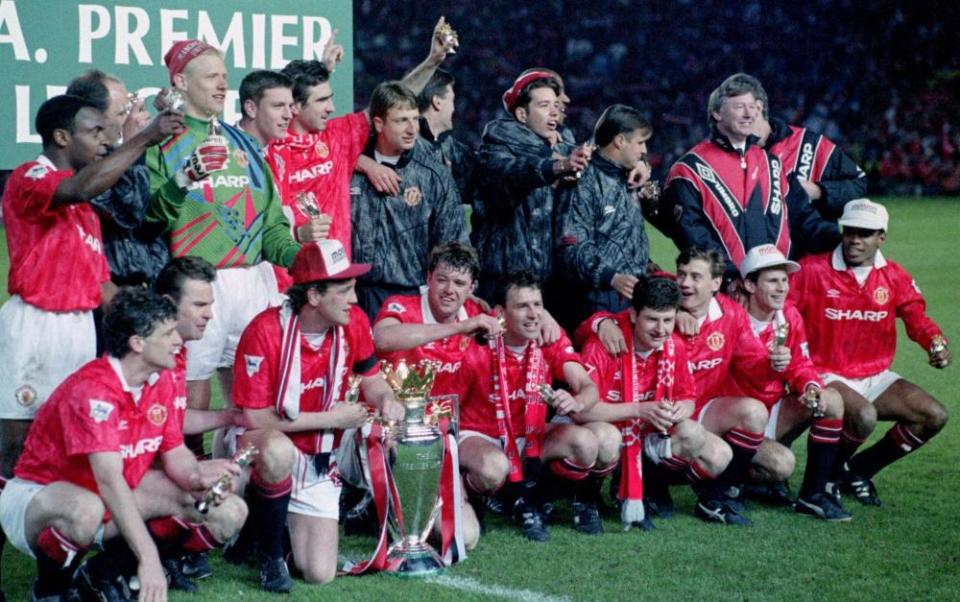

Without Ince, there would have been no title win for United in 1992‑93, the first of Ferguson’s 13 and arguably the most emotional, given that Sir Matt Busby lived to see it and Bryan Robson was a part of it as he neared retirement and it ended a 26-year wait. Eric Cantona was the catalyst; Ince was the basis.

More broadly, Ince was central to one of the most enjoyable periods in United’s history, beginning with the 1990 FA Cup win – the one that saved Ferguson – and taking in the 1991 European Cup Winners’ Cup success and culminating in the domestic double of 1994.

“The 1992-93 title started a cycle of winning trophies at United,” Ince says. “Sometimes people talk about the Class of 92 but the Class of 92 was the team that won that title. It wasn’t Becks and Neville and Butt. I know what they’re trying to do but the Class of 92 was that team that started the ball rolling.

“I think the 94 team was definitely the best of the modern era at United. People keep saying the 99 team but half of those players wouldn’t get in our team – apart from maybe Becks.”

Would Ince be viewed differently had he not joined Liverpool in 1997 on his return from Inter, where he excelled? Most likely. There are some United fans who struggle to forgive him for the way he celebrated an 89th-minute equaliser against them at Anfield in 1999.

“You always get the same thing: ‘Oh, I used to love you as a United player and then you went to Liverpool,’” he says. “I say: ‘Hang about. I didn’t go to Liverpool, I went to Inter Milan. And I didn’t want to leave United. They sold me.’ Also, when I came back from Inter, United could have taken me back. They had first refusal on me.

“I have a wife and children. I have to put food on the table. So if Liverpool’s the club for me at the time … And Liverpool were great. Their fans took me in and didn’t even mention the Man United thing.”

Ince is most proud of how he rose from a tough background in Dagenham to bestride the European game, winning 53 England caps – seven as captain. The most famous image of his career came during the 0-0 draw with Italy in Rome, which secured England’s qualification to the 1998 World Cup. Bandage around his head, blood all over his white shirt, it made an irrefutable point – whenever Ince crossed the white line, no-holds-barred commitment was guaranteed.

“I’ve got that shirt in a frame in my snooker room – with the blood still on it,” he says. “All I know is that when I set out to be a footballer … because people don’t understand my background. When you’re from a tough background and all you want to do is be a footballer, you want to achieve that.

“People are going to like you, people are not going to like you. But one thing I got from my career is that if you ask any fan about me, they will always say I gave blood.”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport