Power in danger of squeezing out skill in rugby union’s battle of big hits

The chairman of Augusta International, Fred Ridley, this week expressed his concern that modern golfers were smashing their way through courses and damaging the sport’s ecosystem: power was elbowing out skill through improved athleticism and technology.

Rugby union has the same problem. As various surveys are made of injuries and concussion – the latest on the latter by Cardiff Met University noted that those who were looking to lengthen the season should bear in mind the injury-risk implications following a significant rise in concussion rates over four years – the increasing size and power of professional players is a contributory factor.

Players were more naturally fit rather than gym-built in the amateur era, not having the time for conditioning programmes. Added to statistics that show that each rugby generation is growing by 2.5cm in height and 4.5kg in weight, well above society’s average, the big are only going to get bigger. It is estimated that by the time of the 2031 World Cup, the average height of the All Blacks will be 195.4cm and 119.3kg, an increase of 10 per cent from the 2011 vintage.

Players may have been transformed physically since the game went open in 1995, but the pitch is still the same size, at least 94m and no more than 100m in length and between 68-70m wide with the in-goal length 6-22m, and the number of players in each side has remained at 15.

Add eight replacements for each side – 18 benches were emptied in the 15 matches in this year’s Six Nations when only 17 players were unused, while in the Premiership this season the emptying rate is exactly 50 per cent, decreasing as the season has gone on and injuries lead to weaker benches – and the old factor of teams tiring in the final 20 minutes and gaps opening up rarely comes into play.

Only one prop played the full 80 minutes in the recent Six Nations, Scotland’s Simon Berghan, and the only hooker to do so was Scottish, Stuart McInally, also against France at a time when their head coach Gregor Townsend was grappling with front-row injury problems. England’s captain Dylan Hartley started four matches and left the field after 52, 51, 55 and 57 minutes.

There is pressure on World Rugby to consider limiting the number of replacements allowed to take the field but the injury rate restricts its options. Permitting them only when a player is unfit to continue would not be popular with coaches and, unless an independent doctor was present at every top tier club match and international, it would not be enforceable. Cutting the number of players on the bench is an option, but there have to be three front rowers under the laws, although scrums are now taking up less and less time, and the flip side is that players carry on despite being injured, as used to happen with concussion.

Safety was the ostensible reason for rucking being given the boot, but its disappearance coincided with the need for television and sponsorship income. Image triumphed over tradition, the sight of bodies being trampled not considered acceptable for the non-squeamish or corporates whose knowledge of the game did not extend much beyond the shape of the ball.

And so instead of bodies being trodden on – the bit in the laws about staying on your feet in a ruck was often forgotten – sentinels guarding a breakdown are now smashed out of the way, sometimes when they are not braced for the collision. It is an act which, if perpetrated on someone standing in midfield would earn a penalty at least and risk a card of some colour depending on how high the contact was made.

Safety? A prone player on the wrong side of a ruck years ago was at less risk than someone either attempting burglary at a breakdown or aiding and abetting. Collisions are seen as an integral part of the game, as rucking used to be, and the bigger players become, the more impactful they are with all the consequences.

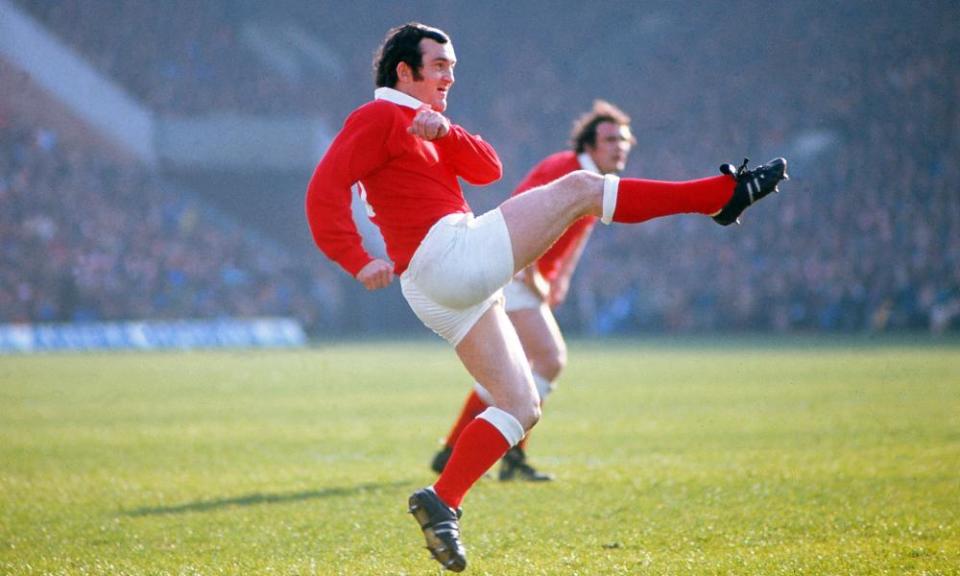

Big hits are lauded in a game that has forsaken its roots. Lunchtime on Tuesday was spent in the company of Phil Bennett, the former Llanelli and Lions outside-half, who was known for his ability to avoid contact and lose opponents in space. He is like a ball-boy compared to modern players and if he were playing today would have to bulk up and tackle to have a chance of making it, but how is it progress when the game does not see such artistry as an asset?

It was Bennett who started that try for the Barbarians against New Zealand in 1973, dancing out of danger near his own line and leaving a sprawl of tacklers cursing him, a memory far more enduring than an incredible bulk crashing into an opponent. Today, although not at the Scarlets who have reconnected with the past while not abandoning the present, he would receive a rollicking for not hoofing the ball downfield.

Golf is concerned about losing its nuance and so should rugby. As golf courses effectively become smaller because of the driving power of the leading players, so a rugby pitch has effectively become smaller because space is more readily filled with forwards no longer obliged to compete at the breakdown en masse and with the fitness to do so.

Administrators are preoccupied by injury rates, as they should be, but it offers the chance for them to re-evaluate the essence of rugby union. It has to be digestible to the paying audience that sustains current wage levels, but in what sport has skill been a turn-off? When it comes to Bennett, more Phil and less Gordon, please.

• This is an extract taken from our weekly rugby union email, the Breakdown. To subscribe, just visit this page and follow the instructions, or sign up above.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport