The Tour de France rules: What do all the jerseys mean and just how do riders go to the toilet?

There are some sports you can switch on and grasp what's going on within a few seconds. They've scored more goals, she has more points, he's in front of him, etc.

The fact that a tennis game went against serve or that one Formula One driver's had more pit stops than another is about as complicated as the tactical situation gets.

Not so the Tour de France. The most famous of cycling's three grand tours is, for many, about as easy to understand as it would be to win on the clapped-out, rusted old Raleigh in the garden shed.

How can a rider win it without claiming a single stage? What do all the different coloured jerseys mean? And just how do they go the toilet?

Terminology is presented here both in English and, for those out to impress, en Français.

The race and its various stages

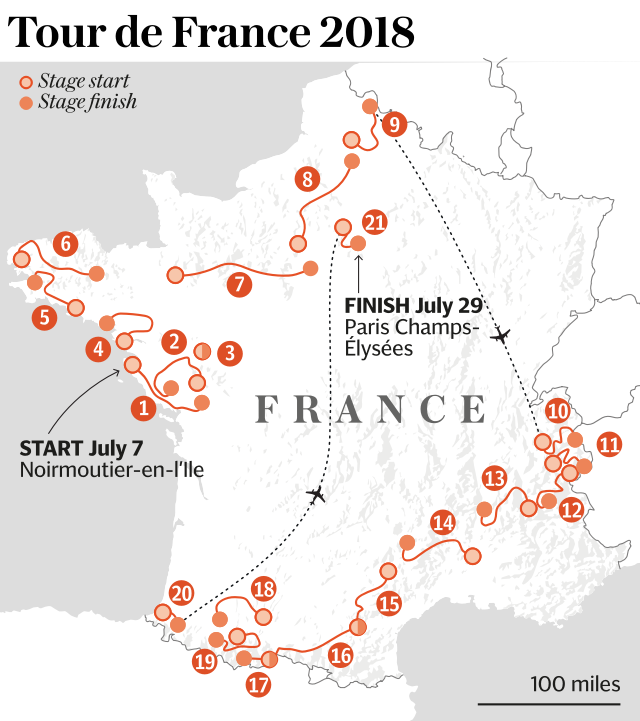

The Tour goes on for three weeks, during which the riders this year will cover 3,351 kilometres – or 2,082 miles – in a rough circuit of the country. It is divided into 21 days of racing, with each day's stage lasting up to five and a half hours and covering up to 230km. Some stages are relatively flat, some torturously mountainous. Each stage has its own winner and offers prize money and points for the first 15 riders across both the finish line and and intermediate line midway through.

The Tour comprises five competitions in total: the general classification, points classification, mountains classification, best young rider, and team classification. The rider that completes all the stages in the shortest time – after time bonuses have been accounted for – over three weeks comes top of the general classification and wins the Tour.

The mountains classification is won on points, which are awarded at the summit of each categorised climb, and on mountain-top finishes.

In the points classification competition, riders are rewarded for quick times at intermediate sprint points during races. More points are available, therefore, on flat stages, with fewer up for grabs on mountain stages.

The general, young rider and team classifications are won by those with the quickest time. More on that later.

Teams and riders

A total of 176 riders start the Tour in 22 teams of eight. Each team is followed around the course by two support cars – one for the main cavalcade of support vehicles and the other in case a rider, or riders, manage to get in the breakaway, from which a sporting director (directeur sportif) can give instructions over the radio, refresh water and supplies, and give mechanical help and replacement bikes during the race. Riders can also get mechanical help from a neutral service car in the event of a puncture or other failure, and treatment from the medical car.

Each team of eight riders will have a leader or protected riders, with the remaining riders – known as domestiques, literally 'servant' riders – responsible for supporting him or them in doing what they do best, whether that's getting stage wins, accumulating points, or going for the overall win.

In the case of Team Sky, they have an overall contender in Chris Froome and the team's job includes protecting him, setting the pace for him, and chasing down attacks by other contenders.

If the leader of the group were a good sprinter say, not in contention for the overall win, the team focus would be getting him near the front of the bunch on stages with sprints.

The different competitions and jerseys

The yellow jersey (maillot jaune): the most important one, as we all know. The famous yellow jersey is worn by the rider at the top of the general classification, meaning they have completed the stages so far in the least time. Wearing yellow in the Tour for just a day or two can be the highlight of a cyclist's career. At the end it goes to the winner.

Contenders for the yellow jersey don't worry about winning every stage, or maybe even any. As long as the riders in front of them on the road are a good way behind them in the overall standings, they will concentrate on where the other yellow jersey contenders are relative to them.

The green jersey (maillot vert): goes to the rider with the most points overall, leader of the points classification. Points are given for the first 15 riders across an intermediate sprint line about halfway through the race and the finish line. All-rounder Peter Sagan has won the green jersey for the past five years.

The polka-dot jersey (maillot à pois): a prestigious garment, this is also known as the King of the Mountains jersey. The red polka dots go to the rider who has won the most points in the mountain sections of stages by reaching the top of categorised climbs first. Like the green jersey system, but specifically for the climbers.

The white jersey (maillot blanc): a junior yellow, basically. Given to the rider under 26 in January of that year with the lowest overall time.

Those are the four main jerseys, there is also the rainbow stripes on white worn by the world champion, currently Sagan, and jerseys with national colours are worn by the champions of individual countries.

Last (and probably least), the team classification, which goes to the fastest team. Measured by the times of the top three riders, the team classification is rewarded with a yellow race number.

A red race number is awarded to the most combative rider of the previous day's stage – someone who has put in a decent attack or two during the day.

Sprints and lead-out trains

Teams built around sprinters often create a lead-out train in the run up to the finish or intermediate sprint, guiding their fast-man through the front of the pack where he can break out from behind his final lead-out man and make a dash for it. Going solo and piggy-baking on other teams' wheels is known as 'freelancing'.

Time trials

The vast majority of the stages of the Tour are long road races, but there are also two or three time trials. Often called the race of truth ('you can't hide from the clock'), they see the riders set off at regular intervals, racing alone against time along a shorter course than normal stages. The time they take on the course is then simply added to their overall time. Special time trial bikes are used for the flatter stages on which riders adopt a different position, designed to be more aerodynamic at the cost of comfort and stability.

Breakaways and attacks

The Tour is a tactical affair. Riders don't simply set off attempting to go as fast as they can at all times. They largely ride together in a main group called the peloton, with small groups breaking away off the front in nearly every stage. It is customary for a group of three to six or so riders to break off the peloton early and go out ahead, often just to reward their sponsor with some time on camera, sometimes hoping they can make it stick for the whole day's racing and take a stage win. The breakaways rarely contain overall contenders, and the peloton will happily let them stray around five to 10 minutes down the road, depending on who's among them, before swallowing them up again when they have tired out.

Attacks, which often take place on climbs, will see a rider suddenly break away from the group he is with and accelerate ahead hoping that the other riders will not be able to stay with him. Domestiques can be vital when leaders attack, pacing them up the climbs and chasing down other attacks by other leaders to try and stay in control.

Crashes

Crashes can destroy an overall contender's hopes in seconds, which is why teams like Team Sky and BMC Racing like to ride right at the front of the peloton where they are least at risk of being taken out by a crash. Riders who get knocked off or held up by crashes in the last 3km of a flat stage are awarded the same time as the rest of the peloton.

Etiquette

The Tour is a gentlemanly affair, for the most part, with riders often slowing down to allow others to catch up after a crash or puncture. Attacking in the wake of such incidents is frowned upon. The yellow jersey is often looked to in such incidents to lead the peloton.

Eating, drinking, using the bathroom

People do get to wondering, with the riders out for up to five hours a day on their bikes, how they eat, drink and use the toilet. Each stage has a feeding station along the way, at which riders will grab a bag (musette) from someone working for their team standing on the side of the road (a soigneur). The bags contain things like energy bars and gels, as well as sandwiches and drinks.

As for going to the toilet, riders will sometimes just take care of business while riding, with other riders taking care not to overtake at the time.

Other times the peloton will generally agree to stop up by the side of the road somewhere discreet, with few spectators, and the cameras will artfully cut away to show viewers a nice bit of local architecture or geography with some historical commentary to boot.

That stuffed lion

One of the most confusing elements of all for the novice viewer: why do they give the yellow jersey holder a stuffed lion at the end of the stage?

Not a symbol of riderly prowess, unfortunately, but the logo of French bank Credit Lyonnaise, which has sponsored the jersey since 1987.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport