The facts of how to win the play-offs: late charges, relegation-form winners and 20% chaos

Arguably English football's greatest innovation of the past 30 years, the Football League Play-Offs remain unrivalled for drama. Barring a tweak to the away-goals rule, the format hasn’t changed since 1990 – and why would it? The conditions are perfect for ding-dong battles and those breathtaking moments that punctuate the nerve-shredding tension. Year upon year, they deliver.

But so fine are the margins between success and failure, it’s easy to buy into the notion that there’s no rhyme or reason to who goes up and who stays down. “The play-offs are a lottery”: it’s one of football’s biggest cliches and biggest myths. Yes, chance plays a significant part. But the probabilities are never equal.

Over the past 27 seasons, there have been 81 play-off campaigns, involving 324 teams, playing 405 matches. And FFT has scrutinised the data to bring you the underlying patterns that indicate why some teams have a much better chance of promotion than others.

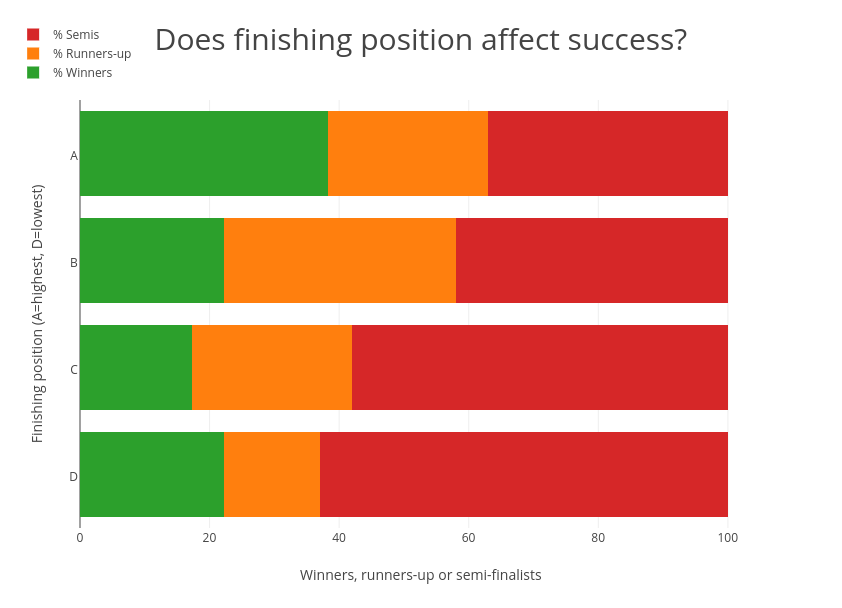

Consider the four participating teams as A, B, C and D (from highest league position to lowest), here’s what you need to know…

80% order, 20% chaos

In the early years, a school of thought developed that teams who finished highest would invariably underperform – most probably because, while the sample size remained small, each instance of Team A failing to win promotion was highlighted as an injustice compared to the way things used to be.

In fact, the opposite is true: on the whole, Team A wins promotion roughly twice as often as everybody else. In 81 campaigns, Team A has triumphed 31 times (38.2%) compared with 18, 14 and 18 promotions for the other three teams respectively. Broadly speaking, that’s a 40-20-20-20 distribution. For every five campaigns, Team A will be promoted twice, everybody else once.

(Key: Team A is in the highest play-off position, D the lowest. Green: winners, amber: runners-up, red: semi-finalists)

The 80/20 principle is another way of framing it, whereby we might conclude that the play-offs are 80% chaos and 20% order. If we take the 40% of Team A successes, you could argue that half of them (20%) are simply the upshot of Team A being overwhelmingly superior, while the other half (20%) are the result of chance (matching the probabilities of triumph for Teams B, C and D).

Which means that sides who have seen the automatic places locked up early - as in this season's Championship and League Two - have more to play for than just maintaining momentum and securing a second leg at home. It might also mean that Scunthorpe's last-day leapfrog over frustrated Fleetwood is more than merely academic.

NEXT: How important are previous meetings? You might be surprised...

Previous meetings count for little

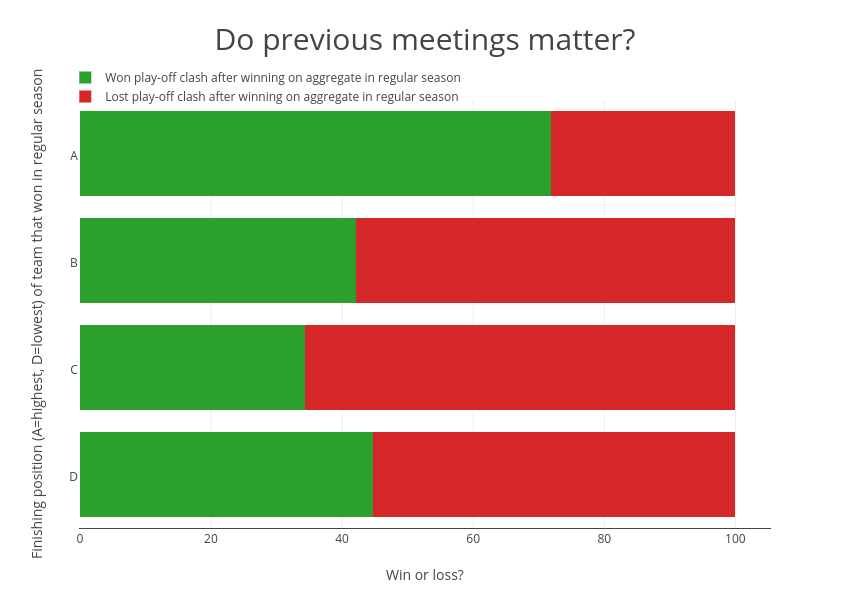

Another popular assumption is that one team has an advantage (be it psychological or tactical) over an opponent if they had the better head-to-head record during the regular season. However, the stats suggest previous results have virtually no bearing. In 193 examples where one team boasted superiority on aggregate over two league games, they replicated that success only 97 times (50.3% – pretty much a coin-toss average).

Play-off results against teams beaten during the league season. Green: winners in play-off head-to-heads, red: losers

When you break that data down by team, a more revealing picture begins to emerge. Similarly to the 80/20 principle above, Team A replicates head-to-head success more than 70% of the time, whereas for everyone else that figure is consistently around 40% – in other words, they're actually more likely to lose than to win. So while Team A might be expected to repeat their triumph over the opponents they bested during the regular season, for Teams B, C and D a positive head-to-head might be considered a bad omen.

Indeed, 2016 provided more examples of this. Despite inferior head-to-heads in the regular season, Millwall overcame Bradford in the semis and Wimbledon beat Plymouth at Wembley - and there was a startling example in the Championship's semi-final between Derby and Hull. Over the two league games, the Rams won 6-0 on aggregate; it mattered little to the timely Tigers, who roared past them en route to promotion.

NEXT: Is terrible form actually a good thing?

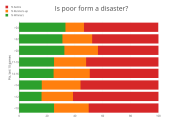

Disastrous form is no disaster

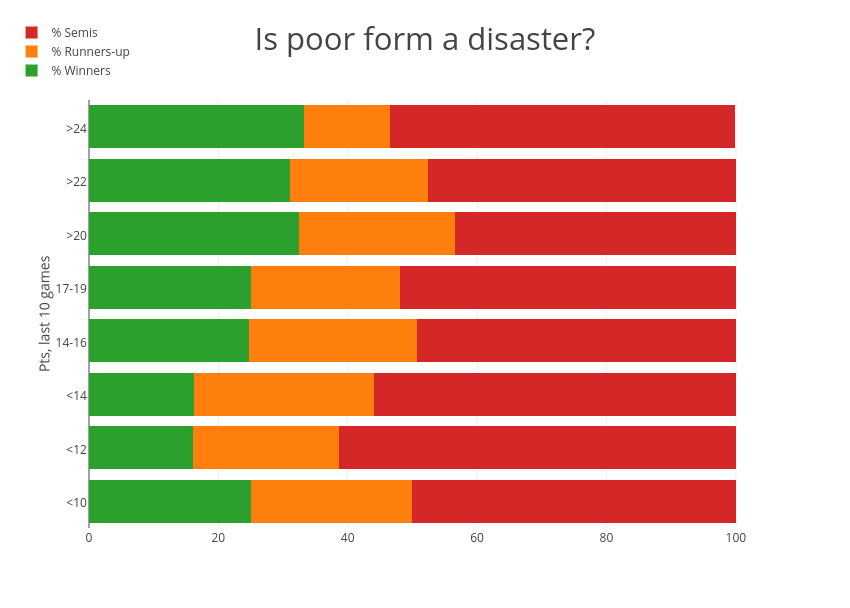

Another statement made so often that it has passed into accepted wisdom is that it's always the team in the best form that wins the play-offs. The figures show that it's simply not true – and there have been examples of the opposite being the case.

There’s no doubt psychology plays a significant role at the end of a gruelling 46-game season, but too much is made of ‘momentum’ – a concept that’s almost impossible to capture by any form of objective measurement. There is a pattern of success in accordance with late flourishes, but the difference is so slight as to be rendered almost meaningless.

How form over last 10 games affects play-off success. Green: winners, amber: runners-up, red: semi-finalists

Intriguingly, though, there’s a small sample where teams have effectively gone into the play-offs in relegation form – taking fewer than 10 points from the final 10 matches – and they’ve performed no worse than chance. Of the 12 such instances, three teams have been promoted (Blackburn 1992, Grimsby 1998, Crystal Palace 2014) and three have finished runners-up.

The obvious explanation here is that expectations become so low as the regular season draws to a close, the pressure on the players is almost non-existent. The prize on offer is no less attractive, yet the ‘no-hopers’ are able to approach their games with freedom.

NEXT: How important is big-match pedigree?

Big-match pedigree matters

A team’s chances of a Wembley promotion are sometimes dismissed on the grounds of inconsistency, where silly results against weaker opposition deem them unreliable. But this isn’t a trait to be overly concerned about here because such teams, by definition, tend to have stronger records against the bigger teams – and that's what really matters in the play-offs.

How form against promotion rivals affects play-off success. Green: winners, amber: runners-up, red: semi-finalists

When measuring teams by their results against the three other play-off contenders and those already promoted via the automatic places, the data shows that those who have excelled against many of their closest rivals have a clear advantage: half of the dozen teams averaging more than 1.9ppg in "big games" have sealed promotion. Of last season's contenders, Barnsley (1.9) had the highest returns and duly went up.

The success rate falls steadily as those hauls drop towards 1ppg, but curiously leaps up again underneath that figure: of the 86 teams to have averaged 1ppg or less against rivals, 24 have achieved promotion and another 21 have reached the final. This was backed up again last year: Hull (0.9) and Wimbledon (0.83) went up, while Millwall (0.9) and Wednesday (0.7) reached Wembley.

NEXT: What about those who enter the play-offs at the last minute?

Late interlopers rule (in the end)

Finally, beware of the free spirit. Late interlopers who gatecrash the Play-Offs in the final few weeks of the season appear to have a psychological advantage over those who have wrestled with the pressure of a promotion race for most of the campaign. But curiously, it’s a phenomenon that doesn’t rear its head until the final.

In 55 instances where a team has occupied a play-off or automatic berth for fewer than 12 rounds after Christmas, 25 (45.5%) have reached the final (44%). But out of those 25, a staggering 17 (68%) have clinched promotion at the Millennium Stadium or Wembley.

How time in the play-off zone affects play-off success. Green: winners, amber: runners-up, red: semi-finalists

It happened again last season, not once but twice. Barnsley had spent just six matchdays in the promotion slots, AFC Wimbledon 11, but they came good when it mattered. Conversely, of the five promo-slot ever-presents, three (Brighton, Derby and Walsall) crashed out in the semis, before Plymouth lost at Wembley and Hull went up.

The best explanation, perhaps, is that the positive psychology stemming from this unexpected opportunity counts for little over two legs against superior opposition. But put those teams on the big stage in a one-off showpiece over 90 minutes, and the idea that destiny is somehow pre-ordained in their favour becomes much more relevant.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport