What the U.S. Did to Japanese Americans Could Happen Again

This past weekend’s Remembrance Day commemorating the unjust detention of Japanese Americans during World War II reminded me of how a law school classmate of mine once questioned why I was wearing a button that read “Executive Order 9066” with an image of barbed wire.

When I explained to him that this was the order issued by President Roosevelt in 1942 ordering the illegal incarceration of Americans of Japanese ancestry as threats to national security following the declaration of war with Japan, he responded: “That was a long time ago, wasn’t it?”

His dismissiveness implied the common belief that historical wrongs won’t be repeated in more enlightened modern times. But such complacency ignores how political and geopolitical circumstances work to hide systemic racism behind the façade of national security.

The circumstances of Roosevelt’s order came at the start of World War II, following the attack on Pearl Harbor in an atmosphere full of heightened military alertness. In the days before the forcible incarceration began, a Japanese submarine had shelled a California oil field and a weather balloon near Los Angeles set off a panic resulting in the so-called “Battle of Los Angeles” in which some 1,400 anti-aircraft rounds were fired at supposed Japanese attackers who never materialized.

Japanese-American Internment & Roosevelt’s Domestic ‘War on Terror’

Following these events, some 120,000 men, women and children were forced from their homes and businesses and sent to isolated “internment camps” in places like Manzanar, California and Tule Lake, Wyoming. Their homes, livelihoods and properties were irretrievably lost.

Shizuko Ina at Kinmon Hall, San Francisco, on April 25, 1942, before being removed from her home and incarcerated with her husband, Itaru Ina.

Relying on the Constitution and rule of law, Japanese Americans like Fred Korematsu challenged the illegal deprivation of liberty and property in the courts. Korematsu—a 23-year-old welder arrested on “suspicion of being Japanese” after defying orders to report to an internment camp because he did not want to be separated from his Italian American girlfriend—took his case all the way to the Supreme Court where he lost. Ultimately, SCOTUS rejected all the internment challenges that came before it, ruling that Executive Order 9066 was necessary in the interests of national security.

Four decades later, it was revealed how Charles Fahy—the Justice Department’s Solicitor General at the time of the challenge—intentionally suppressed information that reports by Naval Intelligence, the FCC and the FBI all discredited the racist theory that Japanese Americans posed a military threat. Fahy ignored warnings by DOJ attorneys and relied upon characterizations of Japanese Americans as disloyal and motivated by “racial solidarity.”

The high court’s decision—aided by the misdeed of then Solicitor General Fahy—continued the legal pattern of treating non-whites as not deserving of full citizenship dating back to the 1790s that had resulted in such anti-Asian legislation as the Chinese Exclusion Act.

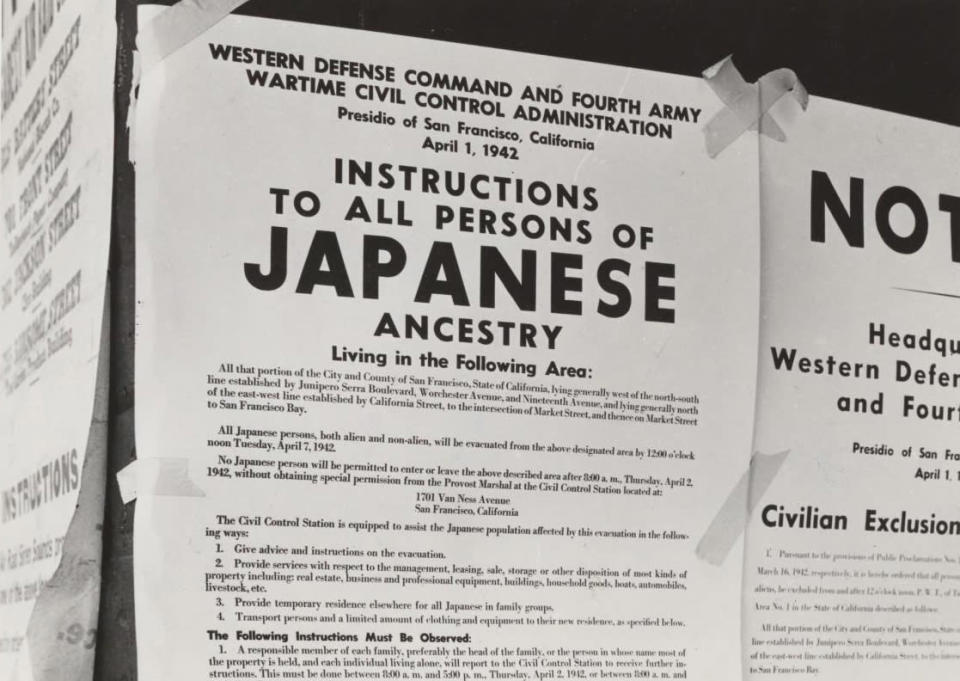

An Exclusion Order posted at First and Front Streets directing removal of persons of Japanese ancestry from San Francisco, California.

As recent executive orders by the Trump administration show, using national security interests to mask systemic racism did not end with the Japanese internment cases. Professor Lorraine Bannai points out that the recent SCOTUS decision in Trump v. Hawaii upholding Trump’s executive order banning travelers from Muslim countries reminds us of the danger of excessive deference to national security interests at the expense of our Constitutional rights.

Noting the government’s refusal to disclose Homeland Security reports that would justify the ban, Bannai notes how in a related travel ban case, federal district court judge Theodore Chuang referenced Korematsu in asking government counsel to represent that there was nothing in the government’s possession that would contradict the need for the travel ban.

Similarly, Justice Sotomayor’s dissent explicitly compared the Trump administration’s failure to disclose the Homeland Security report which outlined the basis for selecting the list of banned countries with Charles Fahy’s failure to disclose the exculpatory intelligence reports in the Korematsu case.

The mess line at Manzanar Relocation Center, California.

The lessons of the Japanese internment are much needed today amidst the growing tensions with China.

Just how tense the atmosphere is can be glimpsed in the recent shoot-downs of unidentified objects following the downing of the Chinese spy balloon—a barrage that echoes the military hysteria of the 1942 “Battle of Los Angeles.” Such a geopolitical tension creates circumstances that too easily allow opportunists to seek power—whether in the form of political support or military budgets—by racial scapegoating.

Don’t Let the Chinese Spy Balloon Become the New ‘Kung Flu’

Guarding against such actions requires rigorous vigilance but it is a vigilance that can only occur if we uncover and study with open eyes the mistakes of the past.

However, actions like Florida Governor Ron DeSantis banning an Advanced Placement course on African American studies seek to undermine the very knowledge and skills needed to guard against systemic racism.

People leave a Buddhist church at the Manzanar Relocation Center, California in 1943.

As shown by reporting in the Washington Post, the College Board removed the word “systemic” from the AP program descriptions involving discrimination and racism. The importance of that word can be found in President Biden’s first proclamation last year of Feb. 19 as a National Day of Remembrance of Japanese American Incarceration in which he pledged a commitment “to eradicate systemic racism.”

My law school classmate’s dismissal of the injustice done to Japanese Americans as something that happened a “long time ago” is a complacency that we need to guard against. But even more dangerous than complacency are the active efforts afoot to rewrite history so that we have nothing left to learn from it.

Get the Daily Beast's biggest scoops and scandals delivered right to your inbox. Sign up now.

Stay informed and gain unlimited access to the Daily Beast's unmatched reporting. Subscribe now.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport