Whatever happened to the maverick footballer?

Any conversation about maverick football players should begin with a definition. The game has now been played for so long and has become so over-covered that even its terms have become dull through overuse. What is a maverick?

In The Footballer Who Could Fly, Duncan Hamilton describes his father’s encounters with Len Shackleton, the legendary Newcastle and Sunderland forward from the 1940s and 1950s: “Shackleton was mischief; he had more colour about him than Matisse. His penchant was for excess; he was purposely as idiosyncratic and playful as possible - the Clown Prince. Why, an England selector was once asked, is Shackleton not in the team? ‘Because we play at Wembley Stadium and not the London Palladium’, he replied tartly, unimpressed by his whimsicality.”

Nearly everything you read about Shackleton is infused with colour. From the portraits of his playing style - the teasing of opponents and his party trick of chopping through the base of the ball, spinning it back to himself - the impression is of someone who loved the game. Not necessarily the winning and glory, so much as the sport itself; the ability to entertain with the ball.

It cost him. He finished his career with just five England caps, with Walter Winterbottom describing him as a “solo merchant” and as someone “who played the way he wanted to”.

Nevertheless, that sense of identity appeared to outweigh any international ambitions he may have had. And within that, his unique set of personal imperatives, lies the essence of a true maverick.

Best by nature

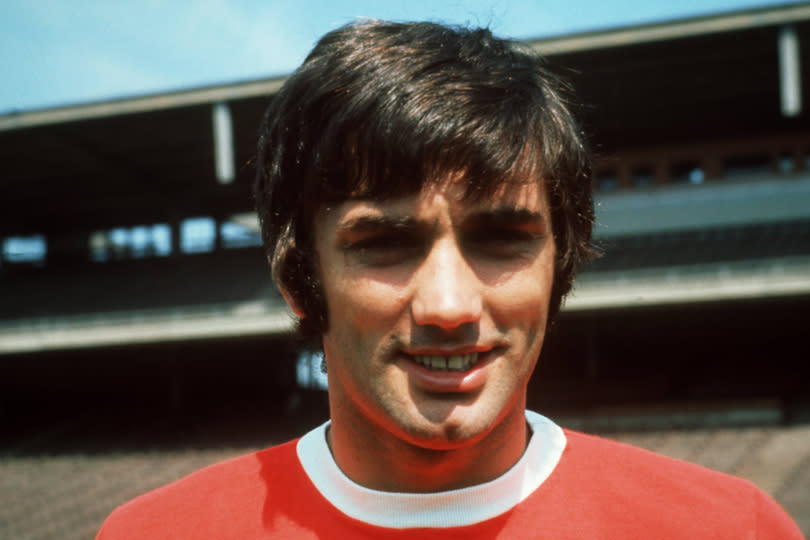

The definition has changed over the years. From the 1960s onwards, the description started to become looser. George Best’s ability to carry possession and humble defenders with the ball – sometimes goalkeepers too – drew obvious parallels with a player like Shackleton.

His playing style, however, seems to have come from instinct and habit rather than any outright desire to entertain. Best was charismatic, but not with the hint of slapstick which would have suggested that his priorities were any different to those of his contemporaries.

It’s an issue confused by Best’s well-documented personal problems. Football fans are romantics at heart and will always gravitate towards relatable players - or those who can perform to a very high level while still exhibiting everyday flaws and vulnerabilities.

In retrospect, Best’s life away from the pitch was likely shaped by a series of crippling neuroses which, when contained within a young body and masked by a handsome face, were easily translatable to devil-may-care charm.

That’s a theme which ran on into the 1970s, where “maverick” became a term applied to players of a certain ability, whose talent was inextricable from a palpable sense of mischief and in spite of less-than-ideal social habits. Stan Bowles, the QPR icon, was the most obvious example. Being a professional footballer was supposed to be the greatest job in the world, and those who made it look like it was - as Bowles must have done - were rewarded with a reverence which lasts to this day.

With each passing decade, the image of the maverick player becomes slightly darker. If Shackleton represented its ideal with his cheeky charm and flamboyance, within 25 years his place in the game had been filled by a rougher cast of characters.

The impression, obviously, is of a sport marginalising anyone who didn’t bow to its utter seriousness. Entertainers still existed, but not in the same way. The notion, for instance, of a centre-forward playing a one-two off a corner flag in Division One during the 1970s would have been absurd. Instead, maverick players gradually become cult heroes, their ‘live fast, die young’ attitudes swirling with ability to create a bewitching effect.

Precisely why that change took place is hard to fathom. Surging professionalism is an obvious explanation, but maybe the growing primacy of the manager shouldn’t be overlooked.

Power of the boss

In Nobody Ever Says Thank You, Jonathan Wilson’s compelling biography of Brian Clough, the myth of him as a laissez-faire tactician is attacked. Clough was evidently eccentric and his match preparation was, by today’s standards, scarcely believable, but he showed little tolerance for players who didn’t bow to his instructions.

While generally viewed as the high priest of intangibles, Clough preached simple but rigid disciplines in which every player had a specific role and the apex of his career, Nottingham Forest’s twin European Cup wins, was achieved through defensive security.

If that is assumed to have been a vague, growing standard across the industry, it’s little wonder that tolerance for exuberance was growing scarce. Clowning came at a cost, failure to win cost people their jobs, and players carving a maverick niche for themselves had less material to work with; interactions with the crowd, maybe, or legendary skullduggery away from the field.

Nearly 30 years further on, football is even running short of that. Certain players have achieved a strain of immortality through loyalty or their role in particularly important moments in a club’s history, but generally the landscape is bare. The occasional high-profile players are forced into the maverick costume, but the result is always an unconvincing fit.

Zlatan Ibrahimovic, for instance, is often portrayed as a modern alt-hero for no apparent reason other than his supernatural ability and a conditioned determination to speak his mind. He’s interesting enough and has been a wonderful player to watch, but his immortality will be underwritten by ability alone.

It would be disingenuous to pretend that football hasn’t changed beyond all recognition, or that a rise in sterile professionalism hasn’t also occurred in every other public-facing industry where great sums of money are at stake.

In this particular case, though, the assault upon the maverick character - the player who wasn’t entirely constrained by the normal boundaries of competition - seems to have come from every direction. From the manager who wants things done a particular way; to the sponsor cash which flow towards pure achievement and a particular type of lifestyle; even to the crowds, who buy their tickets in anticipation of points and victories, rather than the chance to gaze upon any Corinthian spirit.

Players are encouraged to remain within those narrow boundaries from an early age. Crossing over the line between academy scholar and senior professional seems to depend on technical conformity.

Expression breeds suspicion and being too much of an individual, or anything other than a rounded piece which can be slotted into a mechanism, is the fast-track to rejection. It would be naive to presume that such pressures aren’t exerted on personalities, too. The young player is encouraged to be wary - of the media, the public, the pitfalls of a post-internet world - and essentially taught how not to stand out from the crowd.

“Shackleton was a self-confessed non-conformist and show-off, pleasing himself as much as those who watched him," writes Hamilton.

It’s quite a contrast. If a player performed like that today, the chances are that the fans would look on in open-mouthed bafflement. If he was allowed on the pitch in the first place.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport