Why your teams star player is nowhere near as important as you think

In May of last year, Crystal Palace were not one of the surprise packages of the 2015/16 Premier League season. In fact, they limped over the line to finish in 15th place.

That wasn’t the case over Christmas, however. As they tucked into their turkey dinners, Alan Pardew’s team found themselves in the unprecedented position of rubbing shoulders with the top four, kept out of the Champions League spots only by goal difference. Then a 14-match winless streak, featuring five consecutive defeats, transformed the sugar-plum tale of sixth place into the dire depth-plumbing of 16th.

No match was more representative of Palace’s shattering season than their 1-0 defeat at Villa Park in January, which gifted the Midlanders their first victory since the opening day in August. Joleon Lescott headed a corner tamely at goalkeeper Wayne Hennessey but the ball spun from between the palms of his hands to between the heels of his boots, ricocheting about like a housefly pinging between screening and glass in a window. The ball dribbled fractionally over the line. Hennessey’s mistake (along with the bad luck endured by Eagles forward Wilfried Zaha in hitting the post) cost Palace a point or even three, and did less than nothing to boost the squad’s sickly morale.

O-ring Theory

The significance of errors is one of the key facts employed in The Numbers Game to deduce that football is a ‘weakest-link’ sport. A weakest-link sport is essentially one in which the weakest elements of a team do more than the strongest elements to determine the result of a match or a season.

This theory can also help to explain some of the biggest surprises of the previous campaign: Leicester's Premier League title win, Chelsea’s rapid slump to mid-table, the continued success of Diego Simeone’s Atletico Madrid and a Cristiano Ronaldo-less Portugal winning the Euro 2016 final against the hosts and favourites, France.

The conclusion was drawn with the help of an economic model called the ‘O-ring Theory’, which says that if an organisation produces goods or services in which the qualities of each worker’s contributions are multiplied, then mistakes can be catastrophic and success is determined more by the worst employee than the best.

The name refers to the 1986 Challenger shuttle disaster, in which the seven crew members of the NASA Space Shuttle orbiter were killed when the craft exploded 73 seconds into its flight. The cause of the tragedy? A faulty O-ring less than half an inch in diameter.

Arrigo Sacchi agreed with the theory without quite realising it, when the architect of Milan’s success in the 1980s said that the point of tactics is to “multiply the players’ qualities exponentially”.

Player rankings

The O-ring Theory has a couple of important implications for understanding football. For a start, players of similar ability tend to cluster together: squads of galacticos and squads of galoots arise naturally. Because of the higher quality of the surrounding talent, Luis Suarez is even more valuable to Barcelona than he was during his time at Liverpool.

This clustering was visible in last season’s Premier League squads. Using a statistical model called the ‘Anderson Sally Meta-Scout’, driven primarily by match data, every Premier League player’s performance in 2015/16 was rated. A rating of zero means that a player is average within the Premier League for his position; a rating of +0.5 is good, +1.0 is a star, and +2.0 is a superstar.

By contrast, a rating of -0.5 means the player is a serious problem, and -1.0 causes the manager to shake his head, sigh and take a look at options in the youth team. The 11 players who played the most minutes for their club in the 2015/16 Premier League are selected (making sure every position is represented), and the top-rated player is the ‘strong link’ while the 11th is the ‘weak link’.

In general, the better strong links are teamed with the better weak links, and the worse clustered with the worse. The top three teams in the league had weak links who were above average. So, did Leicester succeed against all odds because Riyad Mahrez was phenomenal, or because Danny Simpson performed well as the side’s ‘weak link’?

Best of the worst

The second key implication of the O-ring Theory on football is that, all else being equal, you are much better off improving the tail end of your squad than trying to shoehorn in an expensive superstar. An improvement of equal measure in the quality of your weakest link, as opposed to your strongest, yields a better goal differential, more points and a bigger leap up the table. In other words, even though Mahrez scored and assisted significantly more goals than Marc Albrighton, the former Aston Villa man’s performances relative to his position in Leicester’s hierarchy may have been more valuable.

A big part of Atletico Madrid’s success under Diego Simeone is that he implicitly embraces ‘weakest link’ philosophy. “Football is a game of errors,” he has said. “The fewer mistakes you make, the closer you are to a victory. It’s a lie that he who attacks the most is closer to winning. It’s he who makes the fewest mistakes. And for that, we work on what we feel are the opposition weak points.”

Simeone knows he can’t sign the world’s best players, thanks to his club’s relatively meagre resources, but he realises that he can have the ‘best worst player’ of any club in La Liga or the Champions League, and that he can multiply the qualities of the players he has more dramatically than any other manager.

Then there’s Charles Horton Cooley. Yes, he sounds like a wing-half who represented Sunderland and District Teachers A.F.C. with some distinction at the turn of the last century, but he wasn’t a sportsman. In fact, he was a rather withdrawn, yet renowned, American sociologist.

Still, this unathletic teacher would surely have admitted that football was part of society, and accordingly he might have permitted this variation on one of his most famous quotations. “[Football] is an interweaving and interworking of mental selves. I imagine your mind, and what your mind thinks about my mind, and what my mind thinks about what your mind thinks about my mind […] whoever cannot or will not perform these feats is not properly in the game.”

Still with us? What Cooley’s saying is that the connections between people are as important, or perhaps more important, than the individuals themselves. It is easy to conceptualise the ‘weakest link’ model as focusing just on individual player quality, but that’s the equivalent of capturing tactics in terms of a static formation of 11 single players arrayed in space, the way you’d see them in a newspaper preview of an upcoming match. These atomised pictures are devoid of all of the interweavings Cooley said are so essential to society – and, by extension, to football.

Visualising the network

A more realistic picture of the joined network that truly comprises a football team would have all of the connections, with different lengths and widths representing closeness and importance.

These connections might be actions such as passes or even touching (one academic study actually found that NBA teams who shared more high fives, fist bumps and hugs enjoyed greater success), or they could be the mental interworkings of motivation, cultural difference, personal liking, disapproval, understanding and anticipation. So, while it is simplest to think of a ‘weak link’ as merely the least talented player in the team, a more complex view would be that the ‘weak link’ might actually be a thin, stretched or non-existent link between two players.

Like many a prolific striking partnership, Liverpool duo John Toshack and Kevin Keegan were routinely labelled ‘telepathic’. That tag stuck to the pairing so firmly that they once took part in a televised test for ESP (extrasensory perception). Writing on fansite The Liverpool Offside decades later, Trevor Downey described it thus: “The men were sat back-to-back and given cards with symbols on them. Each had to guess what the other’s card displayed. There was stunned silence in the studio as they made the right call repeatedly [...] Then Keegan collapsed giggling and admitted he could see the big Welshman’s cards reflected in the camera lens.

“Since then, an array of football pundits have continued, undeterred, to pontificate about telepathy between players. It’s a concept that has become embedded in the culture of cliché that constantly lingers around football like a cheap, pungent cologne.”

Leicester's gameplan

Of course, the point is that playing a through-ball, anticipating where the big targetman is going to place his flick-on or covering a team-mate’s position after his ankle is crunched in a tackle is not at all like guessing whether a card has a star or a square on it.

It’s more like sharing an inside joke, being sarcastic (“The gaffer’s in a good mood today”), interpreting a raised eyebrow, or figuring out in a poker game if someone’s raise is a bluff. This kind of mind-reading is omnipresent and makes up the fabric of all social actions. Football requires extensive co-ordination in the most challenging and competitive situations, and social scientists know quite a lot about situations that foster mental interweaving.

Firstly, experience and repetition are usually positive. Leicester’s Danny Drinkwater and Jamie Vardy are not telepathic, but they have played many matches together over a few years and, as a result, Vardy can say of his team-mate: “He knows exactly where I am going to be. Most of the time, he doesn’t have to look. As long as I know the rough area of where it is going to go, I’ll be on my bike and chasing the ball down.”

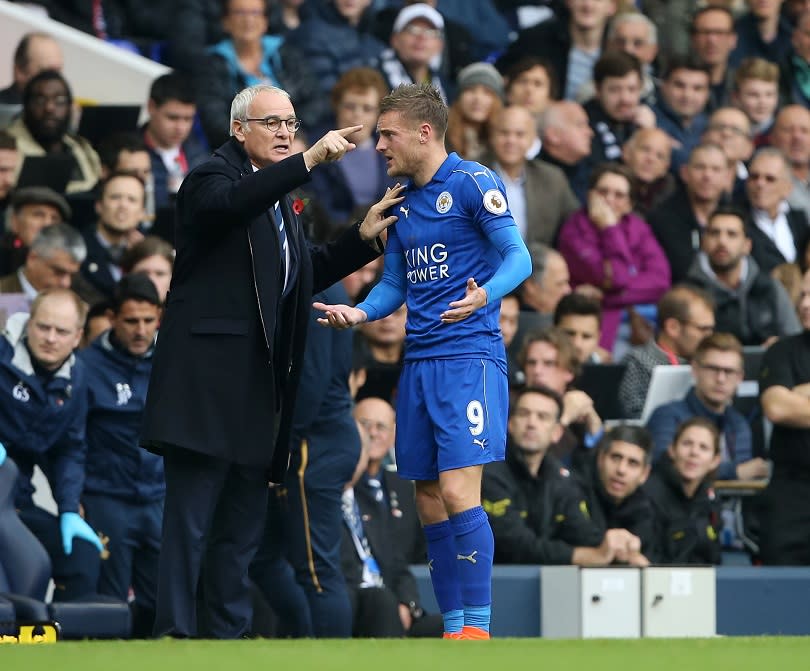

Manager Claudio Ranieri helped this along by being the ‘non-tinkerer’, rolling out the same line-up match after match, and by embracing tactical simplicity: Vardy is always looking to make a break and there are only a few spaces from which he’ll choose.

There is, though, a price to be paid in the longer term for focusing a whole campaign around the same handful of players. Research shows that an exceptionally high number of minutes played in one season is often followed by a much lower number the next. The well-oiled machine breaks down due to injury, fatigue or the departures of players who can’t be replaced. It contributed to Chelsea’s 2015/16 blues and is happening at Leicester now.

The Ewing Theory

There was so much negativity at Stamford Bridge last season;from Diego Costa’s anger to Eden Hazard’s malaise (and maybe fatigue), a surly Jose Mourinho, and lingering court case surrounding the enforced exit of first-team doctor Eva Carneiro.

Studies show that mental ‘interweaving’ is more thorough when the players are in more positive situations: in good moods, with friends, together in close situations. Chelsea could play only ‘literal’ football, while Leicester could put together a poetic, anticipatory, subtle, inferential game. Ranieri dilly-dinged, dilly-donged good vibes and Drinkwater said: “There isn’t a secret: it’s just that we’re a bunch of lads that get along. We are all willing to work hard for each other on the pitch.”

Simeone has the same thought process at Atletico Madrid. One profile revealed: “At meal times he wants his squad sitting at one vast table face-to-face, rather than divided into groups on smaller tables.”

The Ewing Theory, popularised by the American sports writer Bill Simmons, is an anti-strong-link idea named after former New York Knicks centre Patrick Ewing, based on the success that his college and NBA teams seemed to enjoy whenever he was unavailable to play. Simmons described the two critical elements as follows: “A star athlete receives an inordinate amount of media attention and fan interest, and yet his teams never win anything substantial with him.

“That same athlete leaves his team – either because of injury, trade, graduation, free agency or retirement – and both the media and fans immediately write off the team for the following season.”

Simmons has never specified how or why the Ewing Theory works. There are a number of possible mechanisms. First, the attention given to the superstar could lead many to underestimate how good his team-mates really are. Second, the sport might be mistakenly thought to be a strongest-link sport, instead of a weakest-link one. If it is actually the latter, then the absence of the superstar might be survivable.

Third, the team may be forced to alter its tactics inefficiently in order to keep the superstar active and motivated when he is playing.

Fourth, the doubts of the outside world prompted by the loss of the strong link provide some extra motivation to the remaining players, who give the proverbial (but unmathematical) 110%. Cristiano Ronaldo’s numerous championship wins, vastly outnumbering Ewing’s, suggest there could never really be a ‘CR7 Theory’. However, when he finally had to be stretchered off with a knee injury during the Euro 2016 final against France, there was an opportunity for football to add more weight to the Ewing Theory.

You are the weakest link

All the mechanisms were at play during the remaining minutes of the match. No longer having to feed Ronaldo the ball to ensure that he could make incisive runs and shoot, Portugal shifted to a more defensive 4-1-4-1 formation that finally began to challenge France’s dominance in midfield.

His team-mates felt an upsurge in motivation. “Everybody was in shock,” explained right-back Cedric Soares, “but at half-time Cristiano had fantastic words with us. He said: ‘Listen, people, I’m sure we will win this, so stay together and fight for it’. It was unbelievable. All of the team had a fantastic attitude and showed that when you fight as one you are much, much stronger.”

Finally, France were a different team after Ronaldo’s departure. It was as if they thought football is a strongest-link sport, so their chances of victory had increased a great deal. In reality, though, France’s odds had increased by only a few percentage points.

Why? Because football is an interweaving of both the minds and the bodies of the players themselves and the variety of physical and mental connections among them. In short, football was, is and remains a weakest-link game.

This feature originally appeared in the October 2016 issue of FourFourTwo. Subscribe!

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport