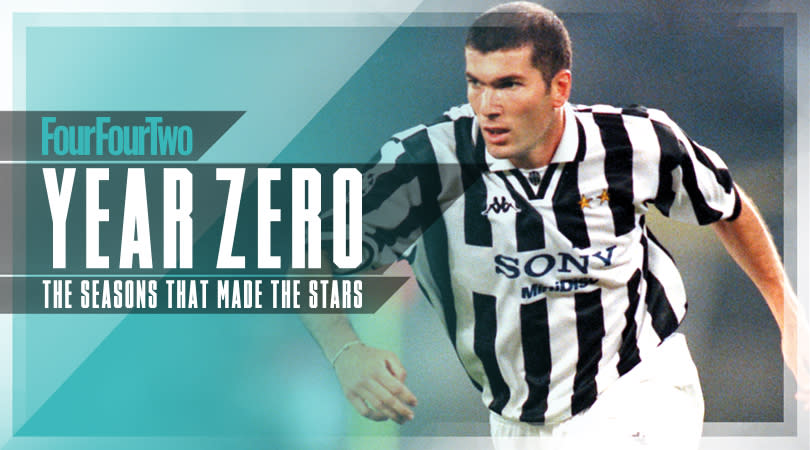

Year Zero: The making of Zinedine Zidane (Juventus, 1996/97)

In the first of our new weekly series examining the turning point in the careers of great footballers, we begin with Zinedine Zidane in 1996/97.

Zinedine Zidane had been warned. Before agreeing to join Juventus in 1996, he phoned up Didier Deschamps - already a fixture in the Bianconeri’s midfield - for advice on what he could expect in Turin. His France team-mate spoke enthusiastically about the club, about Serie A, and about the manager Marcello Lippi. But he also mentioned a fitness coach by the name of Giampiero Ventrone.

By the end of that summer, Zidane would understand of why Juve’s players more often referred to this particular tormentor as the ‘Professor Marine’. “Deschamps did tell me about the training sessions but I just didn’t believe they could be as bad as all that,” he later confessed to the Italian media. “Often I would be at the point of vomiting by the end, because I was so tired.”

Even making it to the finish was an achievement in itself. Ventrone used to hang a ‘bell of shame’ wherever Juventus trained, to be rung by the first player who quit - as some inevitably did - unable to stay the course.

Zidane, though, was no shirker. He had come to Juventus because he wanted to push himself, not stay at Bordeaux and win, in his words, “the cup of nothing”. Those grim afternoons spent dry-heaving beside a practice pitch in Pinzolo were the precursor to something much better.

This would be the season when a skinny 24-year-old took his definitive turn towards superstardom; the one where Zidane became Zidane.

Greatness and destiny

It can be tempting, for those of us who have never competed in elite level sport, to believe that greatness is bestowed on an athlete rather than earned. Italians even have a word, ‘predestinato’, to describe those individuals who appear to have been destined from the start for great things.

There is no question that Zidane had rare natural gifts – childhood friends joked that he seemed to have “a hand in place of his foot” – and yet there are countless stories out there of similarly precocious youngsters who never make good on their talent.

Zidane had played in a UEFA Cup final and represented France at a European Championship in the year before he joined Juventus, but he was still a very long way from winning a Ballon d’Or.

There are countless tales of clubs who supposedly turned down the chance to sign him. In 1995, the late Blackburn chairman Jack Walker is said to have argued that he had no need for Zidane “because we have Tim Sherwood”. Ahead of the 1996/97 campaign, football agent Barry Silkman claimed to have offered the player to Newcastle, only to be told that their scouts didn’t even think he would be good enough for the English second tier.

Such stories are most likely apocryphal, and should be taken with more than a pinch of salt. But it is true that Juventus’s 7.5bn lira (roughly £3.2m) investment in the player was criticised in Italy. The deal with Bordeaux had been struck before Euro 96, where Zidane performed poorly and became a scapegoat for France’s semi-final defeat to the Czech Republic.

Early struggles

He continued to struggle through his first few months at Juventus, too. Ironically, given his difficulties keeping up with Ventrone’s fitness programme, the newspaper La Repubblica described him as “a cross-country runner chucked into the middle of a pack of possessed sprinters”.

In part, Zidane was a victim of poorly chosen tactics. Perceived as a replacement for Paulo Sousa, he was slotted into the middle of Lippi’s 4-3-3 - a deep-lying playmaker with Deschamps and Antonio Conte serving as his muscle on either side. Zidane had a hard time imposing himself on the game from this position, too often getting bypassed altogether.

A shift in Juventus’s shape helped to turn his fortunes, though it came about more through circumstance than any great managerial intuition. Conte ruptured his knee ligaments whilst on international duty for Italy against Georgia in October, prompting Lippi to rearrange his team into a 4-4-2.

By this point, Zidane no longer even appeared to have a secure grip on his place in the starting XI. He was dropped for a Champions League game away to Rapid Vienna, before being restored for the next match, at home to Inter in Serie A.

Whether by design or simply unfamiliarity with the new scheme, Zidane wound up creeping forward from midfield into a not-quite-No.10 role. From here, behind the attack, he excelled – tormenting Inter’s defenders with his direct runs and fancy footwork. After Vladimir Jugovic gave Juventus the lead, Zidane sealed a 2-0 win with a stunning left-footed drive into the top corner from the edge of the D.

Goal at six minutes in

That victory became a turning point. By January, the same Italian journalists who had slated Zidane were eating out of his hand. Gazzetta dello Sport even reported that his neighbours were enjoying living next door to him better than they had the previous tenant, Gianluca Vialli, since he was less prone to kicking up a racket.

It was a different story inside Juventus’s Stadio delle Alpi, of course, where Zidane was increasingly adept at whipping fans up into a frenzy. On April 23, he led Juventus to a 4-1 rout of Ajax in the second leg of the Champions League semi-final.

If Zidane had a signature performance of 1996/97, then this was it - an astonishing virtuoso display in which he set up three goals and then scored the fourth, drawing Ronald de Boer into a collision with his own goalkeeper, Edwin van der Sar, before passing the ball into the open goal.

No longer could Zidane be mistaken for some callow youth. This was one of the very best players on the planet.

Final fall

It is an enduring regret for Zidane that he was unable to follow that display up with something similar against Borussia Dortmund a month later. Juventus lost 3-1 to the Bundesliga club in what became the first of two consecutive defeats in Champions League finals.

Even so, Zidane could console himself with the knowledge that he had lifted the Scudetto, the UEFA SuperCup and the Intercontinental Cup during his first season in Turin. He himself would later describe this season as a turning point in his career.

“Lippi was like a light switch for me,” Zidane recalled. “He switched me on and I understood what it meant to work for something that mattered. Before I arrived in Italy, football was a job, sure, but most of all it was about enjoying myself. After I arrived in Turin, the desire to win things took over and never left me.”

That is the same Marcello Lippi, of course, who later ensured that Zidane’s playing career ended on a defeat, steering Italy past France in the 2006 World Cup Final. You might call it a further validation of the warning Deschamps had issued him 10 years before: these Juventus coaches will make you better, but don’t expect them to spare you some pain.

Next week, Year Zero: Fernando Torres (Atletico Madrid, 2002/03).

Now read...

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport