Barry John, Wales and British and Irish Lions legend, dies aged 79

Farewell to The King. Barry John, the former Wales and British and Irish Lions fly-half who was regarded as the first superstar of rugby union and was convinced to retire because of a young woman’s curtsy, has died at the age of 79.

John’s international career spanned only six years, between 1966 and 1972, yet his brilliance on the field caused him to be named in the same breath as fellow greats such as Gareth Edwards and JPR Williams. His death, which follows that of Williams, his iconic team-mate earlier this year, was confirmed in a statement from the John family on Sunday.

“Barry John died peacefully today at the University Hospital of Wales surrounded by his loving wife and four children,” it read. “He was a loving Dadcu [Grandad] to 11 grandchildren and a much-loved brother.”

John, born in Cefneithin, Carmarthenshire in 1945, represented his hometown club before spells at Llanelli and Cardiff. He would also thrive on the biggest stage. Wales won three Five Nations titles, a Grand Slam and two Triple Crowns during John’s time wearing No 10, which was headlined by his starring role for the Lions in their 2-1 series victory over the All Blacks in 1971.

It was on that tour, his second after taking on South Africa in 1968, that New Zealand journalists dubbed John “The King”. However, the gliding, ghosting playmaker would retire the following year, aged just 27. He announced his decision in the Sunday Mirror, explaining that the claustrophobia of fame had become too overbearing and absurd. Some members of the public evidently regarded him as close to real-life royalty.

“I was the first rugby pop star, superstar, call it whatever you want,” John remembered in an interview with Wales Online. “I was third in BBC Sports Personality, then a month later I was the first rugby player to be the subject of This is Your Life. I was coming off the pitch against England at Twickenham and there is Eamonn Andrews with his big red book.

“I didn’t want to retire, but it was the circumstances. People didn’t understand how you had to go to work, how you had to be fit for international-level rugby. I was getting lethargic, tired. You can’t be like that on the international stage, especially at No 10.

“The invitations just flew in thick and fast. I had no time to myself, just knew I wasn’t as sharp mentally or physically as I wanted to be. I was up there [in north Wales] doing a promotion for the bank. Youngsters were out, lots of people to greet me. I said a few words, and as I was being introduced to someone, she curtsied. Not a major one, a little one, but a curtsy nonetheless.

“That convinced me this was not normal. I was becoming more and more detached from real people. I didn’t want this anymore.”

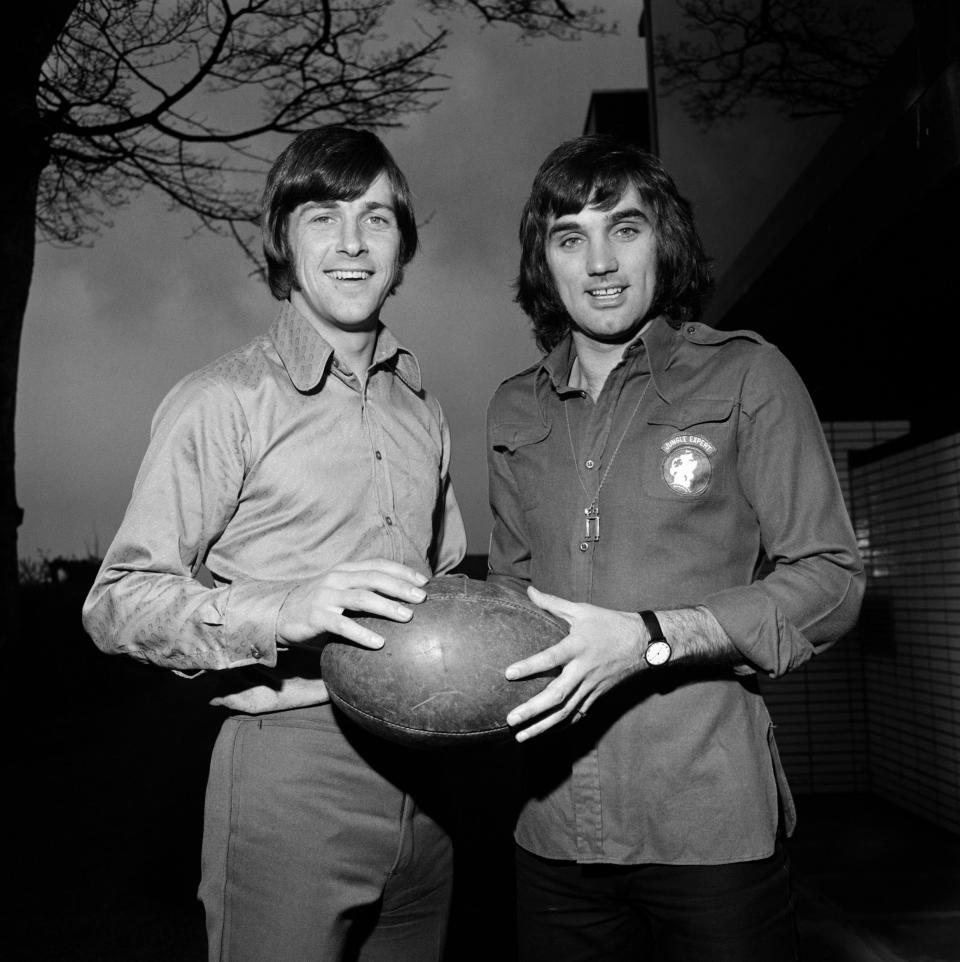

The two figures to beat John into third place in the 1971 BBC Sports Personality of the Year contest were Princess Anne and George Best. John had come to know Best and regarded the Manchester United forward as a friend. Indeed, he would interview Best for his own television programme a few years later.

There is no doubt as to the rich legacy John has left. Edwards, a half-back partner for Wales and the Lions, wrote in his autobiography of John’s assured mind-set on the field. It seemed “a remarkable, marvellous easiness in the mind, reducing problems to their simplest form, backing his own talent all the time”. Rather poetically, Edwards also described a “cool superiority which spread to others in the side”.

The story of the conversation between Edwards and John when the pair met to train together for the first time has been immortalised, too. Edwards inquired about how John liked the ball to be delivered. “You throw it, I’ll catch it,” came the phlegmatic reply.

Gerald Davies, the revered wing of that era, is another to relay awe at John’s ability. “Whilst the hustle and bustle went on around him, he could divorce himself from it all,” Davies once said. “He kept his emotions in check and a careful rein on the surrounding action. The game would go according to his will and no-one else’s.”

At no time was that influence more palpable than in 1971. In the third Test against the All Blacks in Wellington, John scored a try set up superbly by Edwards and the Lions prevailed 13-3. A 14-14 draw at Eden Park in the fourth encounter meant the tourists, coached by Carwyn James, took the series. They remain the only Lions side to win a Test series in New Zealand. As a mark of John’s performances, which featured drop-goals in Christchurch and Wellington, he accrued 30 of the 48 points scored by the Lions across four Tests.

Also part of the captivating catalogue of John highlights is a swerving finish against England in 1969, which arrived off the back of Keith Jarrett’s regathered chip and inspired Wales to a 30-9 thumping that sealed the Triple Crown.

Earlier in the tournament, at Murrayfield, he had charged-down Scotland fly-half Colin Telfer and sold a wicked dummy to go in under the posts. Only an 8-8 draw in Colombes would prevent a Grand Slam, something Wales did achieve in 1971.

Naturally, John was a chief architect, recording points in all four games including tries against Scotland and France. No wonder he intoxicated spectators. No wonder the memories outlasted his relatively short career and will live on for some time to come.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport