Help select the greatest middle-order batsmen in Test history

The shortlist for our all-time World Test XI has been picked by Scyld Berry, our chief cricket writer. Now we are asking you, the readers, to pick the players who should make the final team. We have divided our nominees into six categories:

Openers (pick two here)

Middle-order batsmen (pick three below)

All-rounders (voting on Wednesday)

Wicketkeepers (voting on Wednesday)

Spinners (voting on Thursday)

Seamers (voting on Thursday)

Think we have missed an obvious candidate? Let us know in the comments. Want to justify your selections? Likewise, let us know.

Voting started with the opening batsmen. Today is the election for the middle-order batsmen. Come back on Wednesday to help pick the all-rounders and wicket-keeper and return on Thursday for the vote on the seamers and spinner. The readers' team, alongside Scyld Berry's preferred XI) will be announced on Friday.

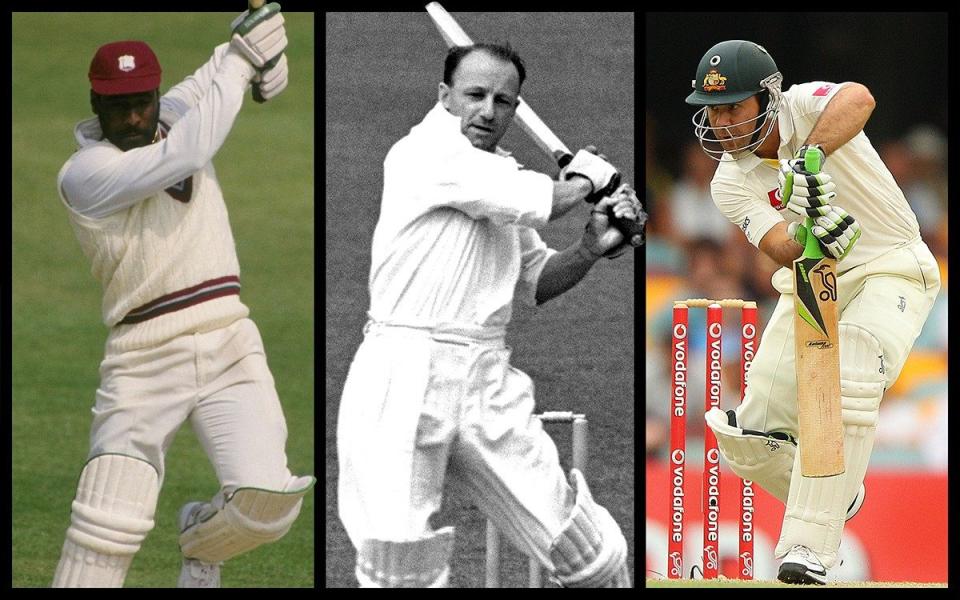

Middle-order batsmen

Sir Donald Bradman (Australia)

Debut: 1928. 52 matches; 6,996 runs @ 99.94 (29 hundreds)

If there is one cricketer who attracts 100 per cent of the votes, it will probably be Don Bradman. One statistic proves his pre-eminence: he averaged all but 100 in Test cricket while nobody else who has played a handful of games – before, during or since – has averaged so much as 62.

He scored 25 per cent of Australia’s runs while he was in the team, the highest proportion ever in Tests; and he made 29 hundreds in 80 Test innings, way ahead of George Headley who scored 10 hundreds in his 40 innings.

So the only question is: where should Bradman bat? If bowling has evolved in other parts of the universe as it has on Earth, there might be some pretty quick bowlers in the opposition, so there is a case for sending in someone else at three, to stare down the quicks and hook them, like Ricky Ponting or Viv Richards, and keeping Bradman for four.

There again, the new technique that Bradman worked out to deal with Bodyline is exactly what batsmen do now when facing a bouncer-barrage: backing away to carve over third man. Even though it was nearly a 100 years ago, Bradman was far ahead of his time and had the answers.

George Headley (West Indies)

Debut: 1930. 22 matches; 2,190 runs @ 60.83 (10 hundreds)

At three, Headley was to West Indies what Bradman was to Australia, contemporaneously, and he did not have the same support (Bradman had Bill Woodfull and Bill Ponsford to wear the bowlers down first). Headley scored 21 per cent of West Indies’ runs when he was in their Test side (nobody else, apart from Bradman, has scored so much as 20 per cent).

If averages are what you want, when the Second World War came, Headley was averaging 66 and it was only because of public demand that he played three more Tests after the war, which brought his average down to 60.83, the fourth highest ever.

When the going got tough or pitches were wet, Bradman would sometimes not want to know, whereas Headley excelled, as with a century in each innings in the Lord’s Test of 1939, or averaging 97 in the 1934-5 series when no England batsman could muster 30. Headley’s defence, on the back foot, was the basis of his game.

Graeme Pollock (South Africa)

Debut: 1963. 23 matches; 2,256 runs @ 60.97 (seven hundreds)

He could hardly have done any more than what he did before the sporting boycott on apartheid South Africa in 1970, when he was only 26. From the age of 19 he was walking out nonchalantly at number four, taking up a left-handed stance with legs astride, and dispatching all bowlers to all parts.

Anyone who can score a Test hundred in Australia at the age of 19 has to be good, and anyone who can score two at that age has to be even better.

Just before the curtain came down, he scored 274 against Australia, the highest innings by a South African before readmission; and Pollock scored his runs at a rattling rate, with more emphasis on boundaries than sprinting between wickets.

As with Barry Richards, how he would have fared against West Indian fast bowlers and Asian spinners can only be speculation, but his 23 Tests amount to a strong body of evidence that he would have found a way. As it is, his Test average of 60.97 is third highest of those who have played a minimum of 20 innings.

Sir Vivian Richards (West Indies)

Debut: 1974. 121 matches; 8,540 runs @ 50.23 (24 hundreds)

Suppose the Martians, or whoever the opposition may be, take an early wicket or two. Out walks a batsman without a helmet. “Who is this Earthling? What does he think he is doing?” This messaging might confuse the Martians and set them back after their early breakthrough.

No batsman ever made such a statement of his own and his team’s superiority as Richards did, before he faced a ball. Chewing gum, pulling on his maroon cap, staring down opponents, taking guard at the crease like a king ascending his throne: without the need for words, or numbers, Richards proclaimed who ruled the cricket field, before whipping the first ball through midwicket.

A few others have scored more runs; nobody has intimidated bowlers more, making batting easier for those who followed.

If any figures are necessary to corroborate: when his passion burned most fiercely, Richards scored 1,710 Test runs in the single year of 1976 - and obviously he scored faster than any predecessor or contemporary, his 100 off 56 balls against England in 1985-6 unbeaten until 2015-6 when Brendon McCullum did so.

Sachin Tendulkar (India)

Debut: 1989. 200 matches; 15,921 runs @ 53.78 (51 hundreds)

His sheer weight of numbers demands nomination: the only player to score more than 14,000 Test runs, or play 200 Tests, or make 100 international hundreds, 51 of them in Tests, again the most. But as impressive as any statistic is this one: he averaged at least 40 in every country that played Test cricket in his career, all 10 of them. No better evidence that his method worked in all circumstances.

Yet there were two Tendulkars: the youthful dasher who judged the length so quickly and attacked, and who ran down the pitch to take Shane Warne apart, then the patient accumulator bent on scaling those summits of 100 hundreds and 200 Tests.

Bradman saw himself in Tendulkar Mark 1, as the batsman who came closest to him in method; and if there have to be two Bradmans or Bradmen in this XI, so be it. Time for one last stat: 34,357 runs in all international cricket!

Brian Lara (West Indies)

Debut: 1990. 131 matches; 11,953 runs @ 52.88 (34 hundreds)

If the word ‘genius’ can be applied to any batsman, then it has to be awarded to Brian Lara: a David Gower with an even higher backlift and more flourishing follow through who made enormous hundreds.

What other word can be applied to a batsman who could utterly dominate Muttiah Muralitharan on his own Sri Lankan pitches, scoring 688 runs in a three-Test series and 42 per cent of the West Indian runs? He was not bad against pace either, especially in his two match-winning centuries against Australia in the 1998-9 series at home.

As for his world record-breaking innings against England, first of 375 in Antigua then of 400 not out, nobody could have made them easier on the eye if not the fielders’ feet.

Being human, he had a fallibility, when the ball was bounced under his armpit around his ears; otherwise he could be supreme when not playing his own inner game. Other left-handed candidates for a middle-order place include Shivnarine Chanderpaul, Graeme Pollock and Kumar Sangakkara.

Ricky Ponting (Australia)

Debut: 1995. 168 matches; 13,378 runs @ 51.85 (41 hundreds)

Has there ever been a better batsman against fast bowling than Ponting? He was raised partly in Tasmania, and partly in the first Australian academy when it was based in Adelaide and he spent his teens hooking fast bowling off less than 22 yards in the indoor nets there.

If he was always a champion against pace, after three poor tours of India his playing of spin kicked on too. He was also, surely, the best-ever fielder at silly point for spin bowling, as brave when standing close-in on the offside, wearing shin-pads but no helmet, as he was when hooking.

As a captain, even though he lost three Ashes series against England, he won 48 of his 77 Tests, so a candidate worthy of consideration for this job too.

Kumar Sangakkara (Sri Lanka)

Debut: 2000. 134 matches; 12.400 runs @ 57.40 (38 hundreds)

He rose above the level of all other Sri Lankan batsmen from the plains, which include Colombo, by growing up in the hills on the bouncier pitches of Kandy and Asgiriya school. His wrists thenceforth were raised higher in the backlift, enabling him to get on top of the bouncing ball and to succeed equally much in the southern hemisphere, as so few Asian batsmen have done.

To this task he also brought his legally-trained mind, so that he visualised each innings and rehearsed against relevant bowling beforehand. This quality was even more necessary for a Sri Lankan who never participated in anything longer than a three-Test series, and who therefore kept on facing new, rather than exhausted, opposition.

The result was that a highly competent wicketkeeper/batsman (he averaged 40 while keeping in the first part of his Test career) averaged 66 as a specialist left-handed batsman; rose to sixth among the all-time Test run-scorers; and finished with the highest average of those who have scored 10,000 Test runs, 57.

Joe Root (England)

Debut: 2013. 129 matches; 10,948 runs @ 50.22 (29 hundreds)

Of the Big Four – Virat Kohli, Joe Root, Steve Smith, Kane Williamson – Root used to be the least: the one who could not convert his fifties into hundreds, the one who averaged below 50. The other three then stalled, whether owing to Covid, or captaincy, or other factors, while Root has forged ahead.

Kohli went three years without a Test century; Williamson went almost two years without one when he had trouble with his left elbow; while Smith was given the elbow after Sandpapergate.

Root has gone from strength to strength, first as the captain of a weak batting side who began converting starts into hundreds, then as elder statesman after he learnt his new role during the winter. Since January 2021 he has scored 12 centuries in 60 innings, and ever more quickly. In his last Test, Root’s assault on Michael Bracewell’s offspin got lost in the wash but it was superlative.

No Test hundred in Australia, true, but nine fifties in 27 innings and an average of 35 there suggests he can cope - and, at 32, he can look forward to another Ashes tour.

As a bowler he is undoubtedly the best of the Big Four; he has 53 Test wickets.

Steve Smith (Australia)

Debut: 2010. 96 matches; 8,792 runs @ 59.80 (30 hundreds)

If the opposition have gone ballistic at the sight of Viv Richards marching out without a helmet, they will go mad at the obsessions and quirks of Steve Smith.

Nobody, conceivably, has twitched and fidgeted more at the crease before the ball was delivered. Then, as it was being bowled, nobody in red-ball cricket can have moved around the crease more than Smith in the middle phase of his career, when he would walk outside off stump to clip straight balls leg side.

“How do you get Steve Smith out?” was the question which circulated round England in 2019 as he scored 774 runs in seven innings. The realisation eventually sunk in: he set up, like Bradman, to hit through the leg side with his dominant bottom hand, so the answer was to bowl a fullish length on fourth stump and tempt him to drive off the front foot, just like ordinary mortals.

Smith’s ban for Sandpapergate ended his full-time captaincy, and his batting became more orthodox, yet the obsessions and runs continue.

Voting is now closed

You can still vote in our poll of opening batsmen. Come back on Wednesday to vote for the all-rounders and wicket-keeper. Then on Thursday select the seamers and spinner. Voting in all polls closes at 8pm on Thursday.

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport