Kevin Phillips: ‘Why manage South Shields? Nobody else would have me’

A nod is all it takes for South Shields’s youth goalkeeper to spring onto the benches and disconnect the speaker. Kevin Phillips closes the door. A modern remastering of I Will Survive stops and a hush descends. “I’m f------ excited,” Phillips begins.

That much is obvious. A morning watching James Martin’s cookery offerings has passed, and now nerves jangle. “A lot of people doubted you,” he continues. “And I tell you what you did, you proved them wrong. That’s what you do in life to doubters: prove them wrong.”

The players follow assistant manager Wess Brown - “Mr South Shields” - and Phillips retires to his office, a small room easily mistaken for a broom cupboard behind the intimate changing area. “I’d love to survey managers about the worst part of match day,” he tells Telegraph Sport during 48 hours of unprecedented training ground and match-day access. “A hundred per cent they’d say it’s this period. Sat in a little office, normally freezing, is horrible.”

Eventually Phillips heads out. A gentle word here, a pat on the back there. The final drill is shooting. Of course. What else? Phillips is up again. “What a f------ opportunity” he begins. Saturday’s opposition were Radcliffe Borough, second to Shields’ first in the Northern Premier League. “Do the s----- things well. Go and do it better than you’ve done all season, and then come back in here and f------ celebrate.”

‘I opened the door fearing the worst’

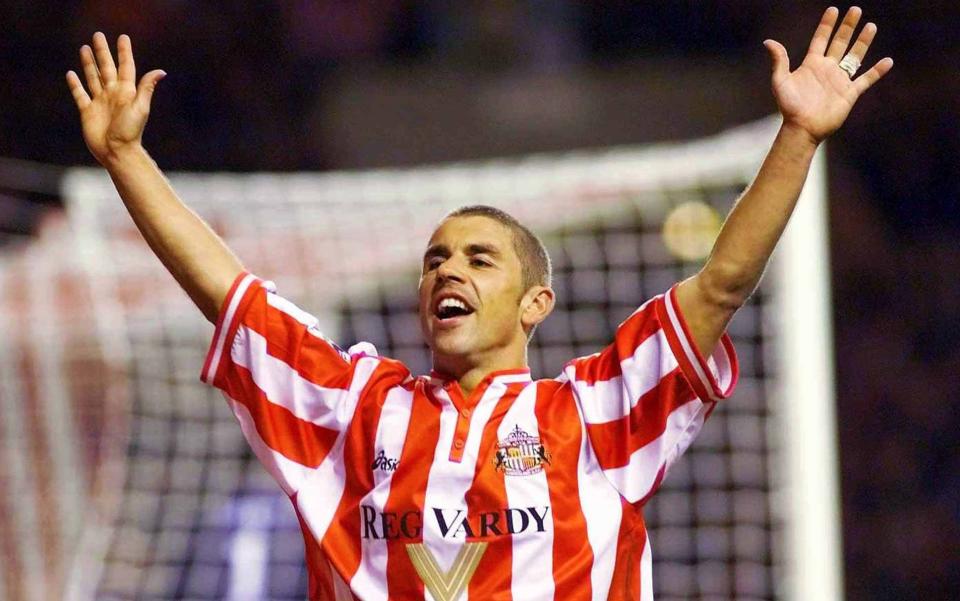

Promotion to the National League, when it comes, may bring Phillips closure. Just 33 days into his reign, tragedy touched him. While a player at Sunderland – where 130 goals in 235 games helped earn the club Premier League status and won him the European Golden Shoe – he formed an enduring friendship with Keith Havelock, a stalwart volunteer at the Sunderland fans' museum. They met over a drink and “got on like a house on fire” says Phillips. “He followed me everywhere. He drove to every away game, and we travelled back together.”

Phillips sought Keith’s counsel when he received an out-of-the-blue text from Geoff Thompson, Shields’s owner, on New Year’s Eve 2021. Keith explained that the non-League club was “going places” and that he “should seriously consider” joining. While Phillips sorted out his own accommodation in Durham – the birthplace of three of his four children – Keith hosted Phillips. And then... Phillips’s cadence slows.

“I hadn’t been able to get hold of him all day,” he begins. “Not unusual, but when I got to his house, his car was there. I knocked on the door. No answer. I knew something wasn’t right. I opened the door to a room on the left fearing the worst. I found him dead.”

Keith had cardiomyopathy and his heart had failed. It is on such moments that life spins. “It left a massive hole in my heart,” Phillips admits. “It took until the summer for me to let it sink in. Football is therapeutic.” So too has been the mutual support of Keith’s daughter Kelly. She has attended every home match since. Against that backdrop, football drifts into insignificance. But Phillips had a job to do.

He had replaced Graham Fenton, who had overseen a triple promotion. Plus, there was the 2017 FA Vase triumph at Wembley. Phillips’s appointment was a calculated gamble by Thompson. True, there was playing pedigree and post-retirement spells coaching at Leicester, Derby and Stoke. But no managerial gig.

Phillips is candid: “Did I ever think I'd get back in? Honestly, probably not.” A break was welcome, but he did not anticipate an extended absence. “People asked why I decided to come in at this level? The simple answer is there wasn’t anything else.”

Not that Phillips was desperate. He was comfortable working in the media. But having met Thompson, and seen what had recently become a full-time set-up, any resistance evaporated. “I would have regretted not taking the challenge,” he says. “Now I’m back in the fold, on the training ground, amongst it, the buzz is back. It’s all I know.”

Phillips’s task is simple: move Shields towards the Football League. It is five years since their last elevation, albeit two were pandemic curtailed. Gallingly, they were a dozen points ahead of the chasers when the 2020 league was voided. A pair of play-off defeats have sandwiched that disappointment.

“I don’t like the play offs,” Phillips says grinning. After a trio of failures as a player, he experienced euphoria in 2013 when netting the winning goal for Crystal Palace. But as Phillips mentally returns to last April’s semi-final penalty shoot-out defeat by Warrington Town, his shoulders tense. “The worst feeling I've ever had in sport. My heart was racing. You’re desperate to get through but can't affect it. I couldn’t watch. Straightaway I thought I’d let everyone down.”

Anyone claiming that this level lacks pressure then, is misguided? “A hundred per cent. You could say there is more pressure than in the Premier League; there, if a manager gets fired, he gets a few million quid and walks into another job. You get fired at this level and that’s your livelihood. I'm under no illusions: if I got sacked it would be tough to get another job.”

After three days’ holiday, Phillips was back at work.

Advice from McClaren – in the shower

Half-time arrives. Phillips and Brown hang back. “That’s the players’ area,” Phillips explains. “I've been there, and I used to think I don’t want the manager to keep coming in. I don’t want to be a pain in the a---.”

Phillips is drawing on a spell in non-League football with Baldock Town, plus 20 years as a pro. From Peter Reid – “he couldn’t manage today, and he knows that. Times have changed!” – to Ian Holloway – “I love him to bits. But some of his meetings went on half an hour. I’m a 10-minute man. The lads hear my voice enough in the week”.

It was, though, a birthday-suit conversation with Steve McClaren that resonated most: “We were, bizarrely, showering and he turned to me: ‘Kev, as much as sometimes you don’t want to, you must love your players. You may think one is an a-------, but you’ve got to show him love, too. That one will keep you in a job!”

Phillips clearly does love his current cohort. That affection is mutual and has permeated the entire staff. They go bowling, they wander along Tyneside’s beautiful beaches. Half the squad live in two club-owned properties. “I want to find out about their lifestyles, their family, what makes them tick. It’s hugely important. If you show them you care, you get that back. And ultimately that brings results.”

His senior players “police” the others, and Phillips is comfortable in the dark: “I don’t want any moles. That’s an absolute no, no.” He leans towards leniency but “can dish it out when I want to.” Not though, in the traditional way: “Eddie Howe takes people into the room next door. That’s good management. Some players can shrink if you dig them out in front of the group.”

Phillips enters and, true to his word, is brief. Break-out groups form, and circles. He jokes about another tardy kick-off: “They’ll fine us again. It was £25 last time!” Then comes a bell and Phillips delivers one final message: “I’m telling you now, this 45-minutes wins you the league. I can f------ sense it.”

‘A few of the young lads probably didn't even know who I am’

Phillips is now comfortable addressing the group, but that has not always been the case. “Frank Lampard and Wayne Rooney have said it. Playing in front of 60,000 people is one thing, but talking in front of 20 all hanging off your every word is another. I still get butterflies.”

Does he remember his opening speech? “I tried to make it light-hearted. A few of the young lads probably didn’t even know who I am! ‘Who’s a Sunderland fan? Put your hand up.’ Half the hands went up. ‘Who’s a Newcastle fan?’ The other half put their hands up. ‘Unlucky lads, you aren’t going to be here very f------ long!’”

For those up to Generation Z, Phillips is “Sewpa Kev” up here. Mid-way through the second half, one hooded individual strolls behind the bench, breaking into a solo chorus of “Sad Mackem B------”. Phillips ignores it. “People are either black and white or red and white. Even now, Newcastle fans call me ‘Sewpa Kev’. People ask if I ever get fed up with it. I’m like ‘I’ll get fed up the day they stop calling me it!’. That means they have forgotten me.”

Shields’s future is bright. Having rescued the club when homeless and facing a bleak future, Thompson’s investment means they now own their ground. The main stand has been redeveloped. They host weddings and have 15 hospitality boxes. An international academy has just been launched. Medium-term sustainability is achievable. This is no “win or bust” project.

True, Shields’s wage bill is the division’s highest, and they are the only full-time side. But they have front-loaded their investment. The assembled squad have well over 1,000 Football League appearances, most notably Gary Liddle, Tom Broadbent, Lewis Alessandra and Michael Woods. Shields offered security, with many on multi-year deals.

“A lot of managers just want to get out of the league now and then worry about the season after,” Phillips explains. “We didn’t. We weren’t being blase or arrogant, but we have planned for next season already.”

And community remains at the epicentre of the future. Shields train at Harton and Westoe Miners Welfare Club before lunching at nearby Epinay School, a specialist centre for children with learning disabilities. A professional club then, which retains its non-League sheen. On the Friday, football operations director Joe Monks receives a call explaining that a high-profile friendly with Sunderland clashes with pre-booked nuptials. Thompson must mediate between departments.

‘We know they are watching us’

The final whistle concludes a goalless draw. Phillips the predator is frustrated, but Phillips the manager knows this point’s value. So, he empathises; he praises; he reminds his lads of the 12-point gap they have established at the top. He expresses pride. He gives them two days off.

🗣 Here are the thoughts of Kevin Phillips on today's draw with Radcliffe 👇https://t.co/WN3JjG92Ox

— South Shields FC (@SouthShieldsFC) March 25, 2023

“I’ve told them they could become heroes,” he says privately. “I’ve had those days. I’d sacrifice my status here for these boys. I want them to walk down the street, head up, chest out. I want that for them. Not for me.”

Phillips wants it for Keith too, and for Karl Newton, a scout who passed away last summer in a hiking accident. In the morning, Newton had been messaging Monks. By afternoon, he had gone. “We know they are watching us,” Phillips concludes. “They would be proud.”

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport