He lost a finger and survived a kidnapping. Then, this climber took on a 9,000-foot ‘death-trap’

With jaw-dropping big wall ascents and a life packed with adrenaline and adventure, climber Tommy Caldwell has had a career worthy of – and captured by – a feature film.

But after an agonizing Achilles injury that resulted in numerous surgeries, bolts in his foot and two years off climbing, Caldwell, then in his 40s, was worried about his future.

He enlisted friend and fellow climber Alex Honnold, famed for his free solo ascent of Yosemite’s El Capitan, to join him on a comeback climb. The trip would see the duo aim to become the first ever to finish a single-day traverse of all five icy granite towers of the Devils Thumb massif, located in the Stikine Ranges mountain range that straddle the Alaska-British Columbia border.

The Devil’s Thumb itself is known as being one of North America’s most dangerous walls, and the five peaks, Caldwell tells CNN Sport, were “probably the most menacing I’ve seen, these big spiky mountains with these ice falls all around, you’re in the middle of nowhere.”

Avalanches and winter storms are the norm in the secluded and wild area, where few have made it to the summit, and history books sadly bear the names of those who have perished in their attempts.

And, to top it all off, Caldwell and Honnold decided to cycle to the start of their journey – a 2,600-mile expedition from Colorado to Alaska that would take over a month.

“It’s one of the more remote mountains in the world, and I wanted this incredible journey to get there,” Caldwell explains. “So that’s why we biked all the way. It was like a case study of whether you could do trips like this by human power. I really liked that idea of not putting those guardrails up – it expands the magnitude of the adventure.

“It’s almost like the mountains have gotten too small for us, in a way, because we’ve gotten so efficient at climbing them,” he adds.

The pair’s adventure has been captured in a new National Geographic documentary, “The Devil’s Climb,” which details their stunning – and sometimes terrifying – journey.

To the outside observer, simultaneously climbing up razor-sharp, ice-covered towers in the middle of the Alaskan wilderness is fear-inducing.

“What I do and what Alex does on a day-to-day basis in our climbing seems pretty terrifying to the world outside of us, I suppose, but to us, it’s kind of normal, honestly. When we think back about the trip, it’s not like the terror that sticks in my mind the most. It’s more this incredible adventure with a friend,” Caldwell adds.

Living life in ‘fifth gear’

Though Caldwell experienced incredible highs in his professional career, the lows have been crushing and enough to dissuade even the strongest athlete.

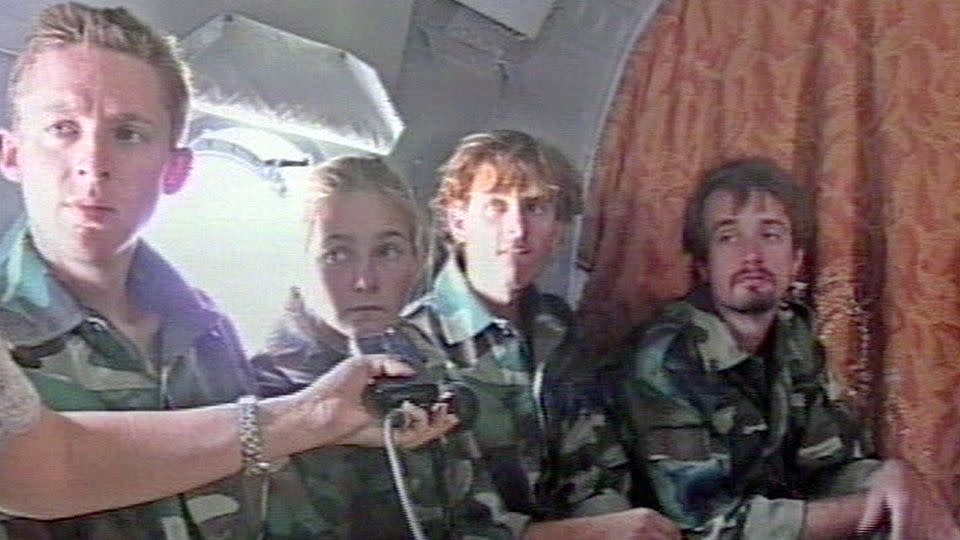

He was aged just 21 when he, his then-girlfriend Beth Rodden and two other climbers were captured and held hostage by members of the Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan while on a climbing trip in Kyrgyzstan in 2000.

For six terrifying days, the climbers were marched at gunpoint through the cold, wet mountains with little food and water, where they found themselves caught up in skirmishes between militants and the army, and left traumatized after watching a fellow captive – a young Kyrgyz soldier who had also been taken – shot dead by their captors.

Then, the group found themselves alone with just one guard and on the edge of a cliff after their captors split up to resupply.

Caldwell made the agonizing decision to push him off, allowing the group to run for safety. For months after the incident, Caldwell grappled with the harrowing belief he had killed a man - though it later emerged he had survived.

After returning from Kyrgyzstan traumatized and wracked with guilt, Caldwell faced yet another setback when he accidentally sawed off his left index finger as he renovated his home. Doctors, he says, warned him this would be the end of his climbing career.

Instead of taking his doctor’s grim prognosis at face value, Caldwell took losing a finger as a challenge, and, eventually, says it allowed him to “exceed expectations.”

“That usually is a pretty big setback for most people, but in some ways, when that happened to me, I was so used to taking these big challenges with me. (I thought) I’m going to use this to bring out my best. And it could be kind of exciting in a weird way,” he tells CNN.

“You feel like that could be so bad, but your body’s amazing, and it has ways of working around it so weirdly. You remove all expectation, it gives you the chance to do better than you think you’re going to do, and everybody else thinks you’re going to do.

“And that starts this incredible flywheel of progression that I find very addicting,” he adds.

Years later, another devastating blow came as he and then-wife Rodden separated. Caldwell then put all of his energy into a feat that most people – climbers included – had thought impossible.

With fellow climber Kevin Jorgeson, Caldwell became the first to free climb Yosemite’s imposing Dawn Wall, the 3,000-foot southeastern face on the iconic El Capitan in 2015.

The incredible feat took 19 days to complete – and seven years of preparation.

The duo used only their hands and feet, with ropes designed only to catch them when they fell. The ascent catapulted them to international fame, even earning them presidential recognition.

“We kind of tend to live our lives in third gear, and when you pick some big challenge, it forces it up into fifth gear. And I’ve become kind of addicted to that,” says Caldwell.

He looks back to childhood adventures with his father – which he explains was like “adversity training” – as one of the foundations from which he built the resilience he is now famed for in the climbing world.

“You become addicted to it, but then, eventually, you’re going to come across things like adversity that you don’t plan. And so if you already have that mentality built into you, it can make it much more easy to manage,” he explains.

Still, life continues to throw curveballs his way. For two years, Caldwell was forced off the wall with an Achilles tendon injury, forcing him to confront the notion that his body might not behave the way it once did in younger years.

“My age isn’t old as a normal person, but if you think about an athlete … 46 is quite old. We’re constantly trying to stay at the top of our game. So I am at that age where I’m kind of like, ‘Oh my gosh, am I going to be able to keep it the same way I have in the past?’” he explains.

“That’s been on my mind. The trip (with Honnold) was a way for me to heal and a way for me to kind of test myself,” he adds. “It did heal me. It helped me feel like I was turning back into an athlete. And overall, it was really incredible.”

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport