‘Passion, performance, poison’: Why this Scottish soccer league is struggling to shake off the specter of religious bigotry

Surrounded by medics, Hibernian FC player Martin Boyle lay on the pitch after diving for the ball in a Scottish Cup quarterfinal earlier this year and landing awkwardly on his head – the then 30-year-old suffered a concussion – an injury he would later describe as having sent him to “hell and back.”

The game was stopped for around 10 minutes, but as medics tended to the injured forward, chants of “die ya Fenian bastard” sung by some fans of the opposing team Rangers FC echoed throughout the stadium in Edinburgh. Fenian refers to a group of 19th century Irish revolutionaries but is widely recognized as a derogatory term for Irish Catholics.

The language mirrors the division caused by centuries of war and strife between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland, in part because of the west of Scotland’s close historical links with Northern Ireland.

“Over recent years supporters’ unacceptable conduct has become rife in Scotland whether that be through the use of pyrotechnics, sectarianism, objects being thrown onto the field of play or through other actions,” Hibernian FC, commonly known as Hibs said in a statement in response to the chanting.

Police Scotland told CNN it had received no reports regarding fans’ behavior towards Boyle. A spokesperson added: “I can confirm a man was arrested in connection with comments being made towards Rangers fans/staff, however, he was released without charge.”

David Scott, director of Nil by Mouth – a Scottish charity that campaigns against religious bigotry – told CNN “sectarianism is something that’s very woven into the game of football.” He explained that “passion, performance, poison” are at the heart of the game in Scotland, with bigoted chanting taking the forefront.

“It was a historic problem born of the Catholic-Protestant divide in Scottish society, especially in the West of Scotland. And it became greatly manifest in football,” Scottish sports journalist Graham Spiers told CNN.

“That in the main has meant anti-Catholic chanting. This is not anti-Protestant. It’s not anti-Asian, it’s not anti-Semitic. In the main, it has been about anti-Catholic and anti-Irish chanting,” Spiers added.

A problem rooted in history

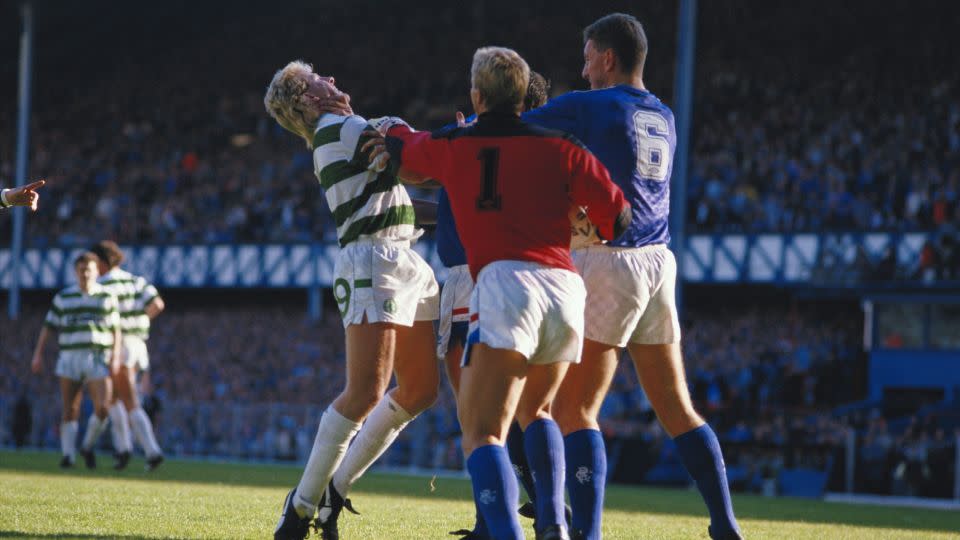

The fierce rivalry between Glasgow’s two most famous teams – Celtic FC and Rangers – is historically one of the most vivid examples of sectarianism in Scottish football, and society.

The two teams play each other in Saturday’s Scottish Cup final.

Historically chants have included anti-Catholic religious bigotry, or vocal support for paramilitary groups like the Irish Republican Army (IRA) and Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF).

Celtic, founded by an Irish member of a Catholic religious order in 1887, wears its heritage proudly in the four-leaf clover of its team emblem.

Meanwhile, Rangers, founded in 1872, was “historically and shamefully” a mostly Protestant club until the 1980s, Spiers explained. “Rangers didn’t hide it, they were proud of the fact they were all Protestant,” he said.

These historically religious identities and rivalries – often described as “Scotland’s shame” – extend to other Scottish clubs, including Edinburgh’s historically Catholic Hibernian and Protestant Hearts of Midlothian FC.

Perhaps the most violent chapter in the sectarian sports rivalry happened in 1995, when 16-year-old Celtic fan Mark Scott was killed by a man who police say had family links to a Protestant paramilitary group.

Scott was wearing a Celtic scarf while walking past a pub frequented by Loyalist fans on his way home from a match on the day of his murder. Jason Campbell was arrested, tried and convicted in 1996 for the killing. He was sentenced to life in prison but was freed on parole in 2011 following human rights legislation.

And though Scotland has become more secular than when these clubs were founded some 150 years ago, “these tribal loyalties remain,” said Nil by Mouth’s Scott.

“When you’re singing and chanting these things, you may think you’re just thinking about your tradition, your background, but actually other people may just hear the hatred and agonism,” said Scott. “Across the city, people will sing songs, ‘We’re up to our knees in Fenian blood, surrender or you’ll die.’

“They will tell you that, ‘This is just theater, these are just words that don’t mean anything, these are football chants,’ that people like me are taking it too seriously. It’s all culture. But it can also be a very intimidating atmosphere to be at,” Scott added.

According to Spiers, Celtic’s support is “maybe 70% Catholic, but with a very large Protestant minority, who are Celtic fans. And they also have songs about ‘Orange [named after King William III, also known as William of Orange and a political society] bastards,’ meaning Protestants.”

Geographically, these are clubs whose support cuts across the geography of Scotland as well as social class, said Scott.

“People don’t go to church anymore,” he added. “People don’t live in these kinds of working class communities in Scotland where they used to do – people are more spread out. I think football becomes this kind of social cement that links people to parts of their past.”

Authorities have tried to tackle the problem, introducing legislation including The Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012, which was repealed in 2018.

“If you’re watching football matches with five or 10,000 people or whatever it is shouting and chanting, you can’t arrest them. So you have to come up with a system of addressing that,” Scott explained.

There were 576 charges with a religious aggravation reported in 2022-23 according to the Crown Office and Procurator Fiscal Service (COPFS), an 8% increase on the previous 12 months.

The COPFS reports that “over the last five years, the number of religious charges reported has fluctuated between around 530 and 670 per year.”

This April, Scotland’s new hate crime law came into force, which focuses on “stirring up hatred,” “racially aggravated harassment” and crimes “aggravated by prejudice” with regard to age, disability, impairment, religion, sexual orientation, transgender identity and sex characteristics – though Scott describes this law as a “red herring” when it comes to addressing bigotry in football given previous legislation didn’t solve the problem.

A spokesperson for the Scottish Government told CNN that it is “fully committed to tackling all forms of bigotry and prejudice including sectarianism.”

The spokesperson highlighted the new Hate Crime and Public Order Act as a mechanism to tackle hatred and prejudice, and said the government would support the police in “taking appropriate and proportionate action to safeguard public safety.”

Joseph Webster, Professor of the Anthropology of Religion at the University of Cambridge, told CNN that his own research shows that the majority of “offensive chanting” occurs when only one fan group is present, in spaces like a social club or pub, and can “foster intra-group solidarity.”

Webster added that his research shows an unintended consequence of the now defunct Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012 “is that those fan bases feel unfairly targeted by the police, and the result is they look inward, among themselves even further, and the chanting then escalates.”

CNN has reached out to Police Scotland, Scottish Football Association, Rangers and Celtic for comment.

Hiding a wider problem

Jeanette Findlay, the Chair, and a founding member of Call it Out, a campaign against anti-Irish racism and anti-Catholic bigotry, said that outrage over anti-Catholic chanting in football is “a long running diversion by the Scottish government, Scottish society.”

“The Scottish government and polite Scottish society don’t like to acknowledge that there is, across Scottish society, geographically and in class terms, a continued anti-Catholic bigotry,” she told CNN Sport, explaining that the vast majority of Catholics in Scotland are of Irish descent.

The Scottish Government referred CNN to its previous statement when asked about these claims.

Findlay says that the government often comments that the problem is contained to football, and by association, areas lived in by the working class.

“Catholics are more likely to live in poorer areas, they are over represented in the prison system, hugely overrepresented in religious aggravated hate crime. We are over represented in certain health conditions,” she added. Scottish government data backs up those observations of Findlay.

In almost half of religion aggravated hate crimes, “the perpetrator showed prejudice towards the Catholic community” (47%), according to a Police Scotland report which reviewed recorded crimes in 2020-21.

The next largest groups were Muslims and Protestants, who each made up 16% of cases, the report data based on a random sample of cases, found.

In 2022-23, police noted that around one in 10 hate crimes were religiously aggravated, though this data set did not disclose which religions were targeted.

Findlay said that, while she has heard hostile chants at football matches, “frankly, I’m more concerned with the employment statistics, and the justice statistics and the health statistics which are more of a problem for us.”

“Someone calling us a Fenian bastard and threatening us on a football pitch doesn’t cause us much trouble.

“If they were marching past places of worship, spitting on our priests and vandalizing our churches, that’s a problem. If they were standing at the door, shouting up, that should be dealt with,” she added.

Journalist Spiers said that, although Rangers “modernized” long ago following pressure from fans and the media, prejudicial songs and their associated meanings “still hangs around Rangers like a bad stench.”

He said, “I’ve been at Rangers games in recent years where the atmosphere has been great – nobody is more sensitive than I am to chanting because God knows I’ve written about it for 25 years.”

But “every so often, it will flare up and we all go. ‘All right. It’s still there. The old problem is still there.’ But it’s not as regular as it was 10, 20, 30, 40 years ago” Spiers added.

“People find it tedious and boring and tragic. I’m not actually offended by these chants, but I’m embarrassed for my country. I’m embarrassed for Scotland, that people will say – why are they singing about Catholics, you know, as if it’s as if it’s the 1920s or the 1890s?”

Webster is one of many who cautions against relying on legislation alone to deal with bigotry, adding: “I think most people would agree that you can’t prevent someone from holding bigoted attitudes by arresting them.”

Celtic recently won the Scottish Premiership, edging Rangers to the title.

Saturday’s cup final offers Rangers a chance to stop its rival from winning the double, but given the clubs’ complicated history, how their respective fanbases behave will also be closely watched.

For more CNN news and newsletters create an account at CNN.com

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport