Why Ivy League Secret Societies and Clubs are More Popular than Ever

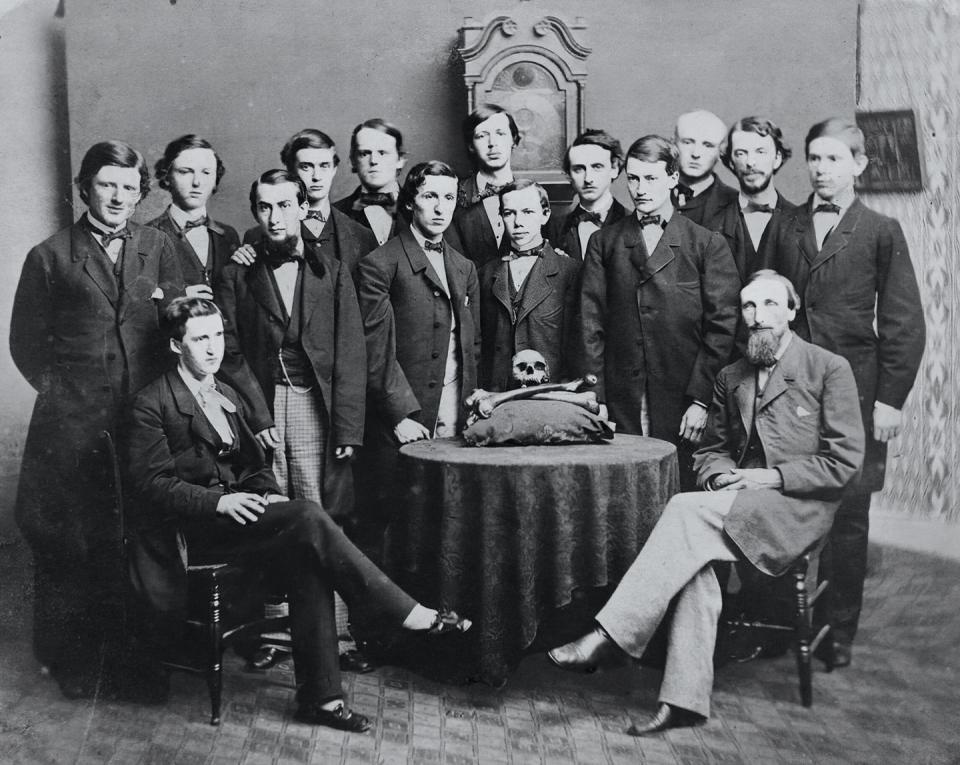

When Sienna was a junior at Yale and was “tapped” to join one of the university’s storied secret societies, they had deeply mixed feelings about it. Members-only societies such as Skull and Bones and Book and Snake, after all, are the pinnacle of exclusivity and privilege at an Ivy League university already defined by the 96 percent rejection rate of applicants every year. Society membership is even more unforgiving. For Sienna it began by being tapped, in the form of an envelope slid under their door, which was followed by competitive social jousting in the form of a drinks date with a couple of members and an interview with the entire society. Then there was the social history of such societies, which are literally walled-off clubs that have been associated over the years with names like Bush, Taft, and Harriman.

None of this jibed with how Sienna (who is nonbinary and asked that we use an alias) saw the world. They had watched friend groups broken up in their senior year—which is when Yale students traditionally join secret societies—because societies intentionally recruit students from different backgrounds and social circles. And Sienna had witnessed the heartbreak that came from not being tapped. “I had friends have mental health consequences from seeing other friends getting invitations slid under the door and not getting any themselves,” they say.

Much has been made in recent months about the tensions and social politics undoing the foundations of secret societies at Ivy League schools. Both the Atlantic and Air Mail ran stories about upheaval within Skull and Bones and how the changing face of the club is causing turmoil with more traditional-minded alumni. And yet when the “fancy envelope stamped with wax” was pushed under Sienna’s door, they couldn’t help feeling intrigued. “It feels very old-school: You’re told to meet some undisclosed people at some random place at a certain time. You’re like, ‘Oh, this is weird and exciting.’ ”

Sienna ultimately joined. “To me it was the appeal of the unknown,” they say, adding that the allure was also “tradition. Yale is very much a campus of tradition. Like, the mythos of the Yale Man: a well-rounded person who is really good at class and does all of these activities.”

The power that private clubs wield over undergraduates, not just at Yale but at Harvard and Princeton—the primary loci of exclusive organizations with multimillion-dollar endowments, arcane initiation rituals, and the promise of networking nirvana packaged as social enlightenment—is improbably strong in an age when inclusivity is a buzzword (not to say cultural imperative) that has redefined industries from Wall Street to Hollywood. And yet even after Black Lives Matter and Me Too, private club membership is booming at these universities, proving that for Gen Z, FOMO and the desire to feel “selected” frequently trump equity ideals, however uncomfortably.

Indeed, as legacy admissions and any perceived door-opening for students of privilege in the wake of the Supreme Court’s ban on affirmative action have come under intense scrutiny, more students of all backgrounds are joining clubs where eligibility has traditionally boiled down to social grooming and money. One Harvard alum who graduated in the mid-1990s says that when she was “punched” (Harvard’s word for being tapped) for Hasty Pudding, one of Harvard’s so-called final clubs, she believes it was because “I had a fancy address on Park Avenue in my freshman facebook” (famously, the print inspiration for Mark Zuckerberg’s digital empire).

Part of these clubs’ enduring relevance is owed to the fact that their memberships have evolved significantly since the George W. Bush days. The current class of Skull and Bones includes only one straight white male. As reported in the Atlantic, at the start of the pandemic new inductees symbolically turned the oil portraits of earlier (white) Bonesmen to face the wall. At Princeton, the prestigious Ivy Club is now known as “Blivy,” owing to a preponderance of members who are “cool, Black, artsy kids who are very woke,” says one Princeton graduate. And certain “bickering” rituals (the Princeton term for the hazing required by the most selective eating clubs, the university’s version of private societies), such as one that involved getting aspiring members’ hair wet, have been done away with out of consideration for hair types that are not Anglo. Another Princeton eating club, Cottage, which was historically the most WASPy (F. Scott Fitzgerald eulogized its members in This Side of Paradise as “an impressive melange of brilliant adventurers and well-dressed philanderers”), now has affinity groups, such as Quottage, for queer members. The group recently had merch made with rainbows arcing over the Cottage mansion.

Yet there is still a discordant truth implicit in being a progressive-minded young person who joins a club that drips with opulence in the form of butlers, bouncers, and cleanup staff, not to mention historic homes. This dichotomy is not lost on members. Yale senior Caleb Dunson, who is Black, has written critiques in the Yale Daily News of the social and economic disparity that exists at the school, where indulgent feasts are held for students while homeless people live on the streets of New Haven. Yet he is also a member of one of the Ancient Eight secret societies. In one op-ed in the Daily News, Dunson explained his position, writing that he seeks “the end of secret societies which, much like Yale, hoard wealth and celebrate exclusion toward no particular end. But I recognize that, for the time being, Yale and secret societies confer power, power which can be used to unravel these institutions.”

Whatever the justification, club culture is alive and well at the nation’s most prestigious universities. At Princeton 70 percent of juniors and seniors join eating clubs with names as unassuming as they are patrician: Cottage, Colonial, Charter. At Yale, secret societies have swelled well past the Ancient Eight to an astonishing 40-plus clubs. And at Harvard nearly half of the male students from the class of 2027 who participated in a survey by the Harvard Crimson said they were interested in joining a final club or fraternity. The final clubs, most of which have brick mansions lining Mount Auburn Street, and the alumni of which include John F. Kennedy (Spee) and Teddy Roosevelt (Porcellian), are by far the most prestigious and desirable social organizations on campus.

“For all their claims of being private, they’re incredibly public about what they’re doing and their events,” says one recent Harvard grad. “The Spee would throw the biggest parties. They’d get these giant ice sculptures with ice luges and pour liquor down them. They’d have open bars and bring in professional DJs for themed parties—Spee Mykonos or Euro Trash.”

Recalling the punch process, one Harvard grad who was a member of the all-female Bee Club says, “It felt at once so stressful but also, like, if I wasn’t part of that process and wanting to be punched then my social life would be ruined at college.”

Universities have tried to do away with private clubs over the decades, or at least dilute their rickety traditions. So even more remarkable than their current popularity is the fact that they still exist. (They operate as independent, nonprofit organizations pumped up financially by generous alumni and members’ dues.) At Harvard the higher-ups have periodically criticized final clubs for their single-gender policies and what a 2017 faculty committee called a “pernicious” influence on campus. But aside from imposing short-term restrictions on members (such as not allowing them to hold leadership roles in other organizations, e.g., captains of sports teams), efforts to eradicate them have been unsuccessful. The university was successful, however, in forcing a few clubs to become coed (six remain all male). And in 2015 Yale attempted to create more transparency and inclusivity within the secret society ecosystem by creating new groups that students could join by filling out a Google doc. There was also a movement to eliminate the term “secret” and simply call the clubs “senior societies.”

But a change in branding can’t undo the thick sense of power attached to, say, Skull and Bones, which selects its members from leadership positions across campus. Or the clubs’ perks: The Bee recently took some punchees on a trip to Paris.

“They own physical real estate,” says Michael Gross, author of Flight of the WASP: The Rise, Fall, and Future of America’s Original Ruling Class of the “landed” clubs. But just as important, “they own mental real estate and social real estate.” Gross recalls giving a talk at Manuscript, the arts and letters secret society that Anderson Cooper and Jodie Foster belonged to at Yale, and how “walking by and looking at those buildings can’t help but tickle your curiosity.”

Real estate is a particularly powerful element for Harvard’s final clubs, which students are punched for in the first semester of sophomore year. Several recent graduates say that because most undergraduates live on campus all four years, meaning there’s no possibility of house parties, socializing is limited to campus gatherings. This was fine until the university began cracking down on those parties in recent years, closing spaces (such as the Molotov Room in Adams House, a traditional favorite) and requiring students who were organizing events to laboriously fill out paperwork ahead of time.

“The way the power dynamic works socially is really about space,” says one Harvard alum. “It’s about where you can go to parties, drink underage, and so forth. The reason I think the clubs continue to hold relevance is precisely that. If you’re not in a club on campus, you have options of maybe going to a school-owned room where there are rules about cleaning up and what alcohol you can bring, versus this other option which is this exclusive mansion where you can go and basically do whatever you want and there are house moms that will clean up and there seem to be endless amounts of money and you have bouncers.”

At Princeton, where eating clubs can be joined in the second semester of sophomore year and operate as advertised—members eat all their meals in them, as opposed to dropping in a few nights a week for events or parties—students feel even more propelled to join one as a form of social survival. “It’s where all the parties are held,” says Samantha Shapiro, a member of Cap and Gown who graduated in 2021. “You go to them your freshman and sophomore year, you see the vibe of them. They dominate campus. In a positive way, once you’re in it’s amazing. You get to see all your friends every day. But as a system it’s awful. It’s fundamentally mean, and it’s exclusive.” The bicker process can culminate in club members projecting a slide of a prospective member’s photo on a screen and debating whether to accept them.

Having a robust social life at college has replaced what used to be one of the primary impetuses for joining an exclusive club: launching a career in politics, on Wall Street, or at a white shoe law firm, during a vodka-soaked weekend retreat at an alum’s summer estate. Today most clubs don’t have a system of formal alumni mentorship, and, according to the Harvard grad, events with older members are more about partying than shmoozing. “You might get very drunk and meet some other college students, but you’re not going to email [an alum] and say, ‘Hey, can you set up a time to interview at BlackRock’ or whatever.

“Maybe 50 years ago there were dinners with an alum sitting next to a college student sitting next to an alum, and they’d have a really civil conversation about career and how the alum could help. Now it’s much more like a fraternity. The favors you’re asking alumni are in the form of paying for dinner for 50 punches versus a job.”

The reality of the job market and DEI efforts across industries has further diminished the importance that an affiliation with an exclusive club once had. “There’s this power shift going on within colleges today, where nontraditional or non–Ivy League colleges are sending a good number of candidates in for entry-level roles like analyst or associate positions,” says Christopher Hunt, president and co-founder of Hunt Scanlon Media, a news source for corporate leaders, in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Years ago, Hunt says, mentioning that you were in a private club like Harvard’s Porcellian “was a significant advantage, primarily because there was a legacy issue. So many of the young people’s fathers and grandfathers had also been in those clubs and advanced through very senior levels of corporate finance or investment banking. Therefore, if Granddaddy was CEO of Morgan Stanley and you all belonged to the same club, you were a good candidate.”

The Porcellian’s reputation as Harvard’s oldest and most secretive, most Boston Brahmin club was underscored last year when a four-minute video of the club’s interior surfaced on TikTok—and was promptly taken down. (Only members are allowed inside the club’s manse.) What was most surprising about the video was how unsurprising it was. The Porcellian remains one of the few all-male clubs left, and the camera moved past wall after wall of black-and-white group photos of club alums. Taxidermy, in the form of mounted deer antlers, abounded. There was a pool table, natch, and bookshelves filled with musty tomes. Time, it seemed, had not touched an iota of the space, which was designed in 1901 by Back Bay architect and Porcellian alum William York Peters.

Even the Harvard Lampoon, which is not a final club but has long been considered one of the most effective campus membership organizations in terms of career launching, has seen its clout diminish. From the 1970s through the early aughts, being invited to join the humor magazine, whose alumni include Conan O’Brien, George Plimpton, and Colin Jost, was seen as a direct route from Cambridge to Hollywood, specifically to jobs on TV shows heavily staffed by Lampoon alums, such as The Simpsons and Saturday Night Live. But as the entertainment industry, too, is seeking to bring in more voices from different backgrounds, that connection is now less clear-cut. “You maybe have a couple people who are maybe working as junior writers somewhere, and they can help you think about your career,” says one young Lampoon alum, “but it’s not what happened 30 years ago, when the head writer was like, ‘Yes, you have a job.’ ”

However, private clubs are still purveyors of subtler advantages sought by many of the nation’s best and brightest college students. There’s the law of averages implicit in joining a club whose members are carefully culled from an already highly curated pool of undergraduates. Skull and Bones is known for plucking members from leadership roles across campus, a practice that can result in “a funny combination of people,” Sienna says. “You’ll have the football team captain and the head of the Women’s Center, which is a queer-friendly space. The idea is to mix people in positions of ‘power.’ ”

“There’s always an underlying evaluation of futurity,” says Alex Borsa, who is a member of Elihu, one of the Ancient Eight societies at Yale. “Of knowing that these are people who, it’s understood that, hopefully, if you encounter one another later in life, you’ll be able to make contact around whatever it is.”

For the former Bee Club member, who is Black, joining the final club was about “proximity to whiteness and proximity to wealth, even though I certainly didn’t have it. That was a big part of the attraction… It’s what I thought being ‘successful’ meant. I had to figure out a way to be proximate to people who had power. That meant trying to assimilate into what the dominant culture was on campus, which was these clubs.”

This person was one of a number of Black members in the Bee, but she said that even so there was not perfect social meshing. Even as an alum, she says, “every year there’s this alumni weekend when everyone comes back, and there’s a big dinner at the house. But after the dinner the Black members would get together and have their own sort of bonding catch-up.”

Borsa was drawn to Elihu because it has stayed true to the “philosophical mission,” he says, of Yale societies, which were founded on civic-minded ideals such as holding hearty debates and discussions. (Skull and Bones still has debates on Sunday evenings.) Elihu is historically among the most progressive, social justice–oriented societies, and Borsa, who is white and gay, appreciated the diversity of his peers and the conversations that came out of their varied backgrounds. “I was able to be privy to a lot of really powerful and beautiful conversations about Blackness and race relations in America. That’s not something I would have gotten out of just any normal social contacts, because those are the types of conversations that happen when there’s mutual trust and vulnerability, which people are not around most of the time.”

For Sienna, in addition to wanting to live up to Yale’s renaissance ideals, they say they joined their non-landed society, which had more of a “frat” vibe, for perhaps the most fundamental reason of all: “There was a fear of, If I don’t do this and all my friends do it, who am I going to hang out with?”

You Might Also Like

Yahoo Sport

Yahoo Sport